This past weekend (November 1-2) at the Museum of the American Revolution’s Revolutionary City (Pre-Occupied) event, I was pleased to represent Magdalen Devine, a feme sole trader in Philadelphia who ran a mercantile business between 1762 and 1775. Devine’s situation in 1775 reflects the tensions and uncertainties felt by many at the start of the American Revolution, and continues to resonate today.

In 1775, Magdalen Devine, “being determined to leave off business,” advertised that she was selling “at Prime Cost, for CASH ONLY, WHOLESALE AND RETAIL, all her STOCK IN TRADE.” Devine first appeared in a Philadelphia newspaper ad in September 1762, selling imported goods with her brother, Frances Wade. By the following spring, the siblings had dissolved their partnership, and Magdalen had set up her own shop in Second Street between Market and Chestnut.

Devine’s ads reflected a keen sense of merchandising, including woodcuts illustrating printed and check fabrics and tightly wound fabric bolts. For more than a decade, Devine imported and sold goods on Second Street, eventually moving into a house she owned that was equipped with “two show windows with very large glass,” probably among the first instances of London-style shop windows in Philadelphia.

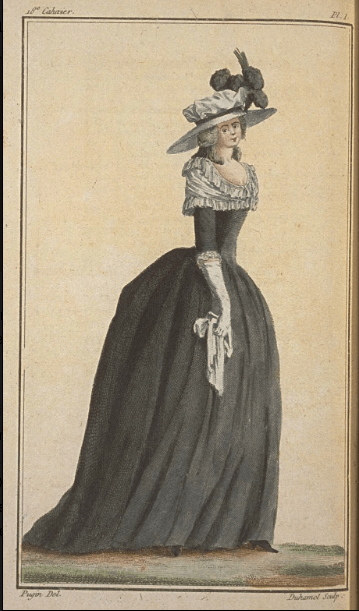

For more than a dozen years, Devine traveled between Philadelphia and London, selecting, importing, and selling “a large and neat assortment of European and India goods.” The chintzes, linens, cottons, and woolens that Devine imported represented the wide range of textiles available, many with specific applications from jean cloth for clothing enslaved workers, tickings for mattresses, and hair cloths for sieves along with the chintzes, taffeties, and superfines that dressed the city’s elite.

By April 17, 1775, she had “determined to decline business, as she intends for England shortly” and published ads in the Philadelphia newspapers calling in debts. Although she initially gave debtors two months (until mid-June), in August she was still in the city and advertising her intention to put debts “into a lawyer’s hands” if not paid within two weeks. An August 30th paper reprinted her ad of August 1, suggesting that the debt collection was not going as she’d planned in April, and the weeks and months kept stretching ahead. The ad placed on August 30th suggests she planned to leave not later than September 15th.

Unfortunately for Devine, mid-September saw a slowdown and stoppage of ships coming in and going out of Philadelphia. By September 18th, no ships were reported outward bound from the city. Magdalen Devine was stuck.

Did she get out on an early September ship bound for Cork or Dublin, and make her way from there to England? Perhaps, but it seems more likely that she miscalculated and was caught in the city as insurers, shippers, and sea captains struggled to make sense of the news from Boston, Providence, and London. Newspapers published English threats to burn all the port cities of the American colonies, and warships plying coastal waters from North Carolina to Maine surely made sailing seem unwise.

Why did Magdalen Devine decide to close her business and leave Philadelphia for England? Just one year before, in 1774, she had acquired the shop with the “two show windows.” What made leaving a good idea? The threads are hard to find, let alone pull, but perhaps her childhood and young adulthood in Dublin suggested that the violence the British were willing to use against a rebellious colony. Famines and strikes in the 1740s prompted British reprisals against a country that served as a laboratory of colonialism.

In the absence of passenger lists, it is hard to know whether Devine made it back to England in 1775, or whether she had to wait until 1783. We know she made it to London, because her death is recorded there in late 1783.

Resources on the English in Ireland

http://www.sneydobone.com/webtree/history-ir.htm

https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/timeline-ireland-and-british-army

https://daily.jstor.org/britains-blueprint-for-colonialism-made-in-ireland/

You must be logged in to post a comment.