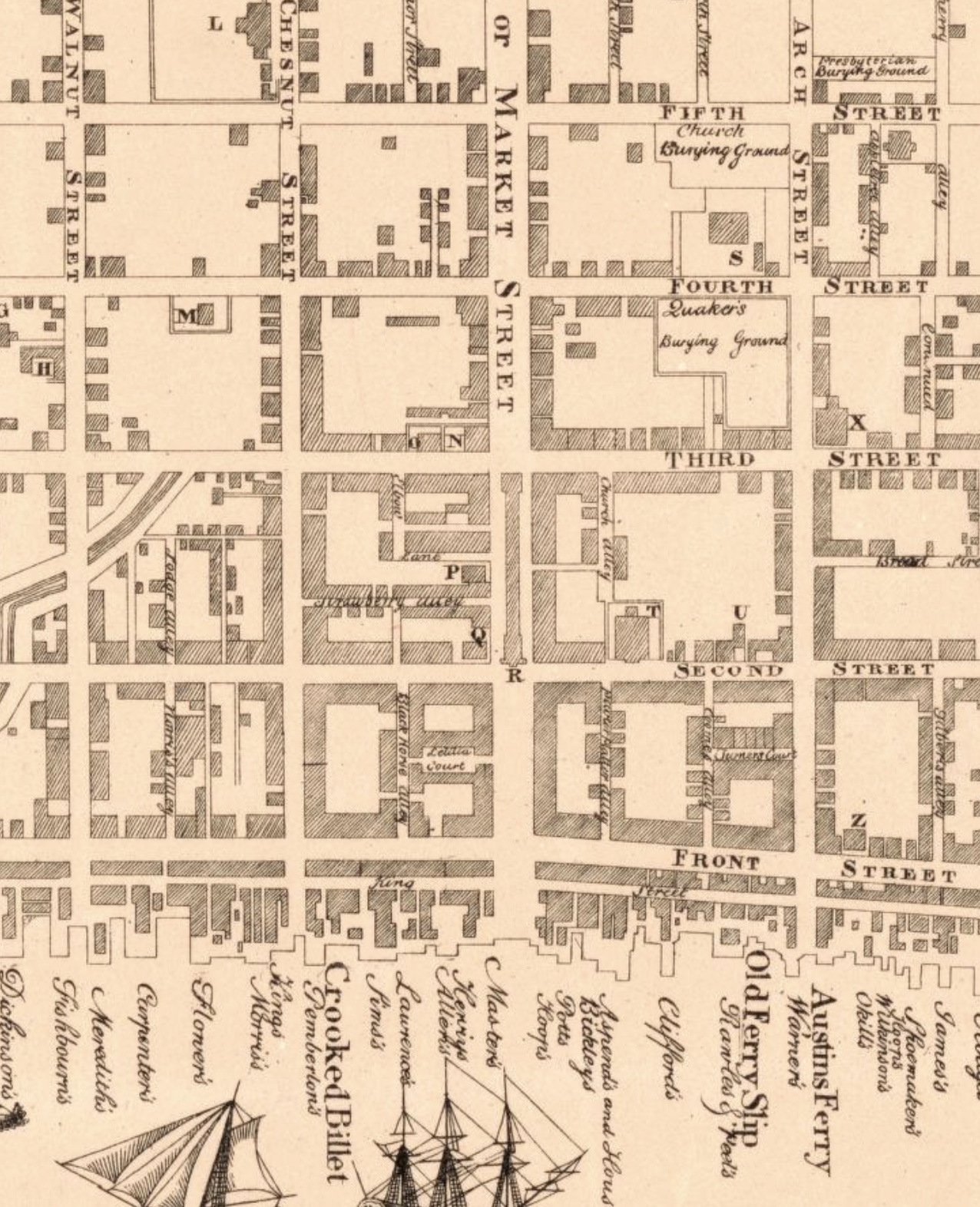

In 1769, Philadelphia had roughly one tavern for every 120 residents. They were clustered most densely in the area Chestnut and High (now Market) Streets, west from the Delaware River to what is now 5th Street. One of the oldest, the Crooked Billet, is called out on the 1762 map of the city by Nicholas Scull, reprinted and now at the Library of Congress. Run for decades by Rebecca Terry, the Crooked Billet primarily served the sailors and men in the maritime trades. Terry was not the only woman with a tavern license in the city—at least three other women, including Sarah Hayes, were long-time tavern keepers.

Sarah Davies Hayes owned two pieces of property on Elbow Lane and another on Chestnut Street; a Quaker, she married Richard Hayes in 1741. He seems to have been a shopkeeper, based on the probate inventory made after his death at the age of 34 in 1748. The inventory includes a side saddle, wearing apparel, a cradle, a fowling piece, and “remains of shop goods.” What kind of shop remains a mystery, as Hayes left no trace in newspaper advertisements beyond an ad placed by his executor in January 1749. Sarah Hayes bought one piece of property on Elbow Lane in 1761, and the second in 1763; the Chestnut Street property was purchased in 1771. Hayes is listed in tavern license petitions for decades (see the Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s Tavern and Liquor License Records (1746-1863)) and appears in tax lists as an innkeeper or tavern keeper from the 1760s until at least 1780.

Tavern keeping was not an unusual occupation for a widow in the 18th century, even if she did not inherit the business from her husband. Some colonies, like Virginia, thought widows particularly well suited to the business, given their skills in household management and stereotype as sensible and moral (and not merry) matrons. In Philadelphia, licenses were issued annually (at a fee of £1/10) to those who successfully passed the scrutiny of the licensing board. (You can see a list of petitioners here.)

The history of the Seven Stars is hard to follow: Benjamin Randolph Boggs (HSP AM.3032) places it at 20 Bank Street, which the Mapping West Philadelphia Project gives as a calculated modern address for property owned by Sarah Hayes, which seems clear enough, though modern streets can be hard to map against historic property lines.* Tyler Putman dug into the history of this parcel and Elbow Lane in general. (Spoiler: there’s nothing to see at 20 Bank Street.) Here’s how Boggs starts his history of the Seven Stars:

“A short distance below the White Horse, also on the west side of the lane, at the spot now covered by the structure know as No. 20 Bank street, stood in very early times a small tavern known as the Sign of the Seven Stars, occupying a lot having fifteen frontage and a depth of fifty-six feet. John Eyre, or Eire, purchased the ground as a vacant lot from Ebenezer Large, currier, on September 19th, 1733 … Eyre was a joiner or carpenter by occupation, and upon his lot he erected a brick dwelling in which he kept a tavern, meanwhile working at his trade.”

After Eyre’s death, his widow, Mary, sold all the brick house and all his other property, as ordered in his will. Jacob Shoemaker purchased 20 Bank Street, lot and improvement and almost immediately re-sold the property to Mary Eyre, who continued to keep the tavern. Boggs describes a number of real estate transactions, concluding with the sale of the property and tavern to Thomas Rogers, “who succeeded her as proprietor.” How this squares with Mary Eyre’s appearance in the 1771 list of petitioners who received a tavern license is beyond me. Bogg’s data comes from Philadelphia Deed Books and newspaper advertisements, though he notes that the Seven Stars “may have been open down to the outbreak of the Revolution, but the newspapers of the period disclose nothing further about it.” (HSP AM.3032, Chapter 20, p. 498-499).

Who kept the Seven Stars? Was it really at 20 Bank Street? Tax records and directories show a lot of taverns and inns on Elbow Lane, so even if the selection of Seven Stars as a name and Sarah Hayes as a proprietor is somewhat random, I know at least that Hayes, the Seven Stars, and the Lane were all real, existed together over three decades, and overlap in some possibly complicated way involving deeds, ground rents, insurance, and competition. Hayes will do to represent the archetype of the widowed tavern keeper of the Revolutionary City.**

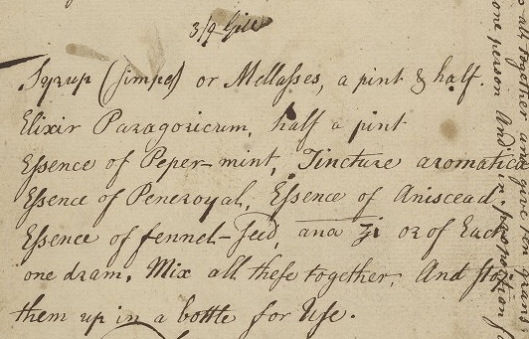

The material world of taverns is much more satisfying to research and compile, though I did get hung up on which shape of bottle held which kind of alcohol, how beer was distributed from the brewery to the customer, and at what level of tavern one would find a Monteith bowl and a silver lemon strainer. The questions are legion: how many glasses? How many mugs? Were basins used on tables the way dishes were washed in early Federal New England? Prices posted or not when the Pennsylvania legislature and provisional government did fix prices in 1778? Some of these questions are answered in paintings from the Sea Captains in Surinam to the John S. C. Shaak Tavern Interior, others can only be guessed at until I find an inventory, if there is one to find.

Then, how do you communicate alcohol to visitors? They can’t taste anything so you can only let them smell the oleosacrum that’s the basis of punch, or the shrubs and cordials popular at the time. Happily, these come in beautiful colors and enhance a table display. My hope with a bench at the table was to invite visitors to sit at the tavern table, and with refinement, perhaps I can achieve that in the future. Reenactors, at least, can bend an elbow at the Seven Stars.

*There’s a compelling argument that someone could untangle the confusion between Jacob Shoemaker’s lot, 20 Bank Street, the lot Sarah Hayes owned, and just who owned the Seven Stars, and where, exactly, it was, but I am not that someone.

**If you are thinking at this point that I have a problem with research and perhaps belabor a question, you are correct. My superpower is overthinking anything.

You must be logged in to post a comment.