Although I’ve portrayed a milliner before, the earliest iteration has been as a shopkeeper in August, 1804, so I thought it best to refresh my knowledge of what 18th century milliners advertised. (Deep dives into bonnets help me focus on bonnets, but necessarily what else was being sold.)

Although I’ve portrayed a milliner before, the earliest iteration has been as a shopkeeper in August, 1804, so I thought it best to refresh my knowledge of what 18th century milliners advertised. (Deep dives into bonnets help me focus on bonnets, but necessarily what else was being sold.)

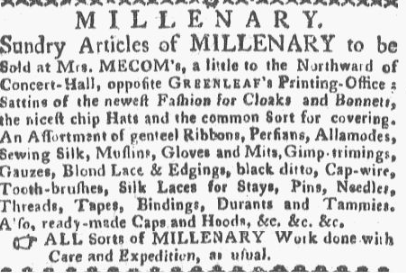

One of my favorite ads is from the January 15, 1772 Pennsylvania Packet. Mary Symonds of Philadelphia published an extensive list of goods, many of which will lead you down a rabbit hole. Three of the listings had particular appeal.

“Womens’ and childrens’ black and coloured silk, Dunstable and chip hats, and bonnets”

“Black and coloured silk” almost surely encompasses the range of colored silk bonnets seen in Boston advertisements, but what’s the difference between Dunstable and chip hats? Price, of course. What most of us think of, or call, “chip” hats should be called Dunstable or simply straw.

Chip hats like the one above in the Snowshill Wade Costume Collection, were made of plaited (woven) thin strips of wood, more like flat baskets or chair seats.

Straw hats, like the one above (also in the Snowshill Wade Costume Collection) are clearly finer than chip and do not need to be covered. The earliest description of the distinctions between hat types that I’ve found thus far is from 1815, in “An Encyclopæaedia of Domestic Economy, Comprising Such Subjects as are Most Immediately Connected with Housekeeping etc etc” which goes into some detail.

The most entertaining discussion I found was in The Sessional Papers Printed By Order Of The House Of Lords, Or Presented By Royal Command, In The Session 4 And 5 Victoriae And The Session 5 Victoriae 1841. The recorded exchange resonates with current discussions of tariffs on imports, but the really revelatory bit is this:

Class distinctions expressed in materials and apparel are eternal.

“Tobines” were new to me (or at least forgotten) and have nothing at all to do with the bishop of Providence. Thankfully, Textiles in America has the answer: “A wide variety of dress materials from fine silks to silk and worsted, and linen and cotton combinations that have warp-float patterns of small flowers or intermittent stripes and dots.” (p 367). Once you’ve seen it, you realize you’ve seen it before.

“Childbed baskets” were also a new concept to me, but The Female Reader, Or, Miscellaneous Pieces in Prose and Verse; Selected from the Best Writers, … for the Improvement of Young Women illuminated the term; the current equivalent is a layette set that includes bedding, and goes beyond the crocheted sweater, cap and booties some of us came to fear receiving. (Mint green acrylic? really?)

It’s a wide range of goods for women to buy (including small accessories for the men and boys in their families), and somewhat beyond the bonnets-hats-jewelry-trimmings we typically associate with milliners. While I don’t have any plans to start manufacturing chip bonnets or making up childbed baskets, I am definitely intrigued by the possibility of expanding my “offerings.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.