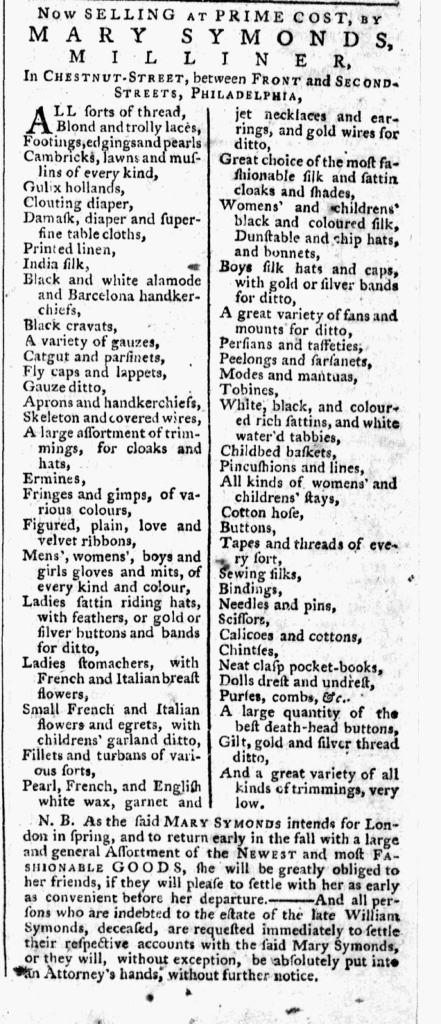

Among the things I ponder about Anne Pearson Sparks is what she wore, and how much clothing she had. She would have seen the latest fashions and fabrics when she traveled to England to buy millinery goods. How did she translate those styles for her Philadelphia customers, like Mrs. Cadwalader, and how did she interpret them for herself? It’s largely unknowable since there are no known images of Anne. Probate inventories provide insights into the quantity and type of clothing women had in the 1770s. They skew higher income since people without wealth had so much less to leave, but given that Anne Pearson owned her own house, and had a £2700 marriage settlement, she certainly had means.

The February 1778 inventory of Mary Cooley’s estate, digitized by Colonial Williamsburg, provides an extensive list of clothing and other items owned by a York County (VA) midwife, including 10 gowns, 6 petticoats, 9 shifts, 5 pairs of shoes (4 leather and one black satin), 15 caps, 9 “chex” (checked) aprons, and 4 other aprons, presumably white. The type of gown is not specified, that is, they are not itemized as “nightgowns,” “sacks,” or “negligees,” though there is an additional wrapper. No bedgowns appear on the list, and there is only one pair of stays. Since only items with value (i.e. sale value) were listed, Mary Cooley’s total inventory probably included bedgowns. The clothing worn by the enslaved woman Bett and her child Peter was also probably not on the list. Bett and Peter appear at the end of the list after items typically found in a kitchen, where they probably worked, lived, and slept; it is likely their clothes were few and had no value.

What does Mary Cooley’s list suggest for Anne Pearson?

The gowns include:

- 1 Brown damask Gown 60

- 1 black Callimanco Gown 60

- 1 Striped Holland Gown 70

- 1 dark ground Callico Do. 70

- 1 Callico Do. £5

- 1 flower’d Do. £7

- 1 India brown Persian Do. £3..10/

- 1 Purple Do. £5

- 1 flower’d Crimson Sattin Do. £12

- 1 Striped Holland Gown 70/

That gives us:

- 2 Holland (fine linen) gowns suited to the hot, humid Tidewater.

- 1 Calamanco (glazed woolen) gown, best for winter

- 1 Damask (probably silk, could be silk and wool) gown, worth 60 shillings ( £3), so less than the silks

- 3 Calico (cotton, probably all printed, one with a dark ground), also suited to Tidewater

- 3 Silk gowns, in “India brown,” flowered crimson satin, and purple Persian.

1959-113-1 Philadelphia Museum of Art

Linen, wool, silk. Living in Philadelphia, Anne Pearson probably had more wool than Mary Cooley; how many more? Would we swap one linen and cotton for two woolen (stuff or worsted or calamanco) gowns? Would we swap a cotton gown for a riding habit? Anne traveled back and forth between Philadelphia and London for years, and a riding habit or (and?) a Brunswick would make sense for travel. With appearance a key part of advertising her trade and reputation, Anne probably had more than 10 gowns, but call it 10 and add at least a riding habit.

Then we add petticoats. Petticoats expand a wardrobe by matching or contrasting with open robe gowns. Six petticoats! That’s a good number of options, but remember, they need to balance the seasons.

Mary Cooley has:

- 1 Pink Persian Quilt

- 1 Black Shalloon Petticoat

- 1 Blue Callimanco Petticoat

- 1 India Cotton Petticoat

- 1 old striped Stuff Quilt

- 1 blue Quilted Petticoat

The pink Persian (silk) quilted petticoat certainly came from a milliner’s shop, and was likely made in England; it could easily be worn with those silk gowns. Having the color here helps us begin to imagine the combinations. Pink Persian and brown damask? Black shalloon and black calamanco? Black calamanco and blue calamanco? The India cotton petticoat was probably worn with one of the calico gowns, and we can contemplate striped stuff with a striped Holland gown. In any case, Mary Cooley’s two, possibly three, quilted petticoats helped her keep warm in silk, calico, or linen. The blue calamanco petticoat might also have been quilted; there are many calamanco whole-cloth quilts, and I like to imagine one as vibrant and shining as this quilt or perhaps this one. Quilted or not, under candlelight both gown and petticoat would glisten.

For mull, I used organic cotton quilt batting. It’s a little thick, but I pull my stitches tight and don’t want the buckram or pasteboard to show too much. The old brim piece served as a pattern for new, though I did have to use a different color for the brim lining.

For mull, I used organic cotton quilt batting. It’s a little thick, but I pull my stitches tight and don’t want the buckram or pasteboard to show too much. The old brim piece served as a pattern for new, though I did have to use a different color for the brim lining.

You must be logged in to post a comment.