In August, the Museum of the American Revolution contacted me about making a snuff-colored cloak. Although many 18th-century women’s cloaks were red, some were not. Newspapers carry ads for stolen goods and runaways in brown camblet cloaks lined with baize; white silk cloaks; black silk cloaks; and cloth cloaks, which are probably “cloth colored” wool– what we would think of as drab or beige. The Museum referenced an ad from the Pennsylvania Gazette of April 30, 1777, May 7, 1777, and May 21, 1777.

“Run away from the subscriber, living in Evesham township, in the State of New Jersey, Burlington county, on the 20th of April. 1777, a certain Sarah McGee, Irish descent, born in Philadelphia; she is about 23 years of age, about 5 feet 7 inches high, very lusty made in proportion; she had on when she went away, a snuff coloured worsted long gown, a spotted calico petticoat, stays and a good white apron, a snuff colored cloak, faced with snuff coloured shalloon, a black silk bonnet, with a ribbon around the crown: She was seen with her mother, in Philadelphia, who lives in Shippen street, where it is supposed she is concealed. Whoever takes up said servant and brings her to her master, or puts her in confinement, so that her master gets her again, shall have the above reward, and reasonable charges, paid by Barzillai Coat”

I was not clever enough to latch onto the snuff-coloured shalloon facings, but I made up a hooded cloak with a snuff-coloured silk lining and dispatched it just before school started. (I doubt I could have achieved a happy color match in any modern “shalloon.”) I’d picked up the wool and silk in Natick, Massachusetts on a summer trip in 2018, and had planned — and put off– a snuff-coloured cloak of my own. Oh well.

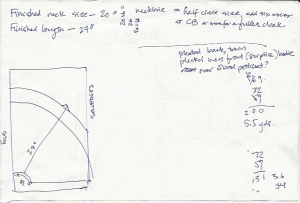

As the semester drew to a close, the cloak started gnawing at me. That was really nice wool! And such a nice color! I really had wanted my own cloak. I succumbed to ordering some substitute wool, and over the winter break, made myself a cloak. They only a day or so, once you’ve done the math to chalk and cut the pieces. I have a handy diagram to help me figure it out, adapted from Sue Felshin’s classic post on cloaks. You don’t need much else.

This wool is heavier than what I’ve used before, and I’m not fully enamored with the drape. Still, this will go a long way towards completing the Cinnamon Toast Crunch Quaker look when I wear it with the brown gown I made this past summer. I love my red cloak, but for a Philadelphia Quaker’s brown gown, a snuff-coloured cloak is a better match.

This wool is heavier than what I’ve used before, and I’m not fully enamored with the drape. Still, this will go a long way towards completing the Cinnamon Toast Crunch Quaker look when I wear it with the brown gown I made this past summer. I love my red cloak, but for a Philadelphia Quaker’s brown gown, a snuff-coloured cloak is a better match.

The making is really simple. You do want to start with a well-made wool broadcloth or coating that will hold a cut edge– that eliminates a lot of hemming, and takes advantage of the natural characteristics of the wool just as 18th-century makers did. You don’t need a lot; I used 1.75 yards of 52-60” wool, which makes an acceptable length cloak even for me (I am 5’-10”).

The cloak neck edge is pleated to a neck size that suits you (annoying, I know, but that’s how this works). The hood is stitched up the center back (I used a butt stitch), with the last 6” or so pleated. This is the trickiest bit. Even strokes make a nice array, but the real trick is stitching the pleats flat so that they hold the shape. Sometimes it turns out better than others; heavier weight wool will be harder to wrangle, as this was.

I ended up piecing the silk for the hood lining (piecing is period) and I’m pleased with how that turned out. I barely had the patience to do it, but the result was pleasing and I saved silk, so there’s that. For ties, I used some silk satin ribbon purchased for some other, now-forgotten project. I tend to save materials, thinking I’m not “good enough” to use them– that is, not skilled enough. Well, if not now, when? The cloak and its ribbon ties mean much more worn than that they will stashed in storage. Eat the cake. Buy the shoes. Make the dress, the cloak, the apron, the ruffles. Make whatever brings you joy.

You must be logged in to post a comment.