At last it has arrived: Wolf Hall. I waited, and did not use a proxy server to watch it early. Just as well that I watch PBS online as I have, thus far, watched the first episode three times.

At last I can understand people’s enthusiasm for historical programs some of us seethe at and cannot watch: my knowledge of the Tudors and their material world is limited enough that I am captivated and not annoyed (except by Anne Boleyn’s wrinkled silk satin bodice, which is striking in its puckers) and I read the books when they came out, and have thus forgotten enough of the details to be merely annoyed and not enraged at changes. (Other, real, critics have caught the language changes in the scene with Wolsey; Mantel is better, of course.)

The third Wolf-watching was with Mr S, who was suitably impressed by the low-light filming. As a former photographer who did a lot of night photography, improper and unbelievable lighting in film does cause an outbreak of caustic commentary. Not this time (he merely noted the fill light on Liz Cromwell’s face in one scene). With 20,000 pounds spent on candles, the BBC did this one right– and lucky for them the advance in camera technology.

But forgot the astronomical cost of all those tapers, that’s not the point: the point is what was believable and how the staging and lighting were used. I believed Wolf Hall all the more because of the low light, indoors and out, matching the time of day. I know how dim it is to light only with candles, and what a pain it is to make them, and how expensive. Light is money, whether you’re paying Ameren, National Grid, or the candlestick maker.

Aside from Hilary Mantel’s brilliant stories and all those candles, what makes this Wolf Hall good television? You know what I’m going to say: the authenticity. No, there are no Tudor accents, late or otherwise; these folks use our vernacular. And excellent arguments can be had about the historical accuracy of Mantel’s characters.

There are other arguments about the material details:

“The dull palette used – presumably in conscious contrast to The Tudors – created an ambience which, at worst, was lacklustre or, at best, homely. And it is that homeliness that concerns me most.

The homely is unthreatening. So, we are invited to view a ‘Tudor world’ as we know it or, rather, as we would like it to be. For instance, I was struck by how classless the society was – social gradation seemed to have disappeared both in the interactions and the interiors. There was little sense (as there is in the novels) of the heavy distaste for a man of such lowly birth as Cromwell’s; there was limited hauteur in a Norfolk or, indeed, the king. Meanwhile, the buildings which were home to Cromwell – still, at this point a lawyer in Wolsey’s service – seemed to lack none of the late-medieval conveniences afforded to the higher born and bettered housed. This is a world which has been domesticated for us so that it is tame, familiar and quintessentially English.”

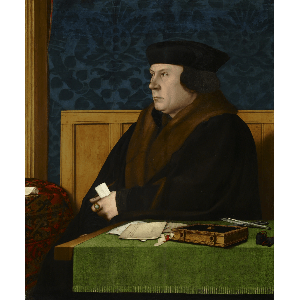

by Unknown artist

oil on panel, late 16th century (circa 1533-1536)

21 3/8 in. x 16 3/8 in. (543 mm x 416 mm)

Purchased, 1882. NPG 668 [Britain}

I know Cromwell ended up with riches but on the BBC he seemed to start ahead of where I thought he was at the start of the novel, mercenary and mercantile background aside.

Still: the spirit of the story and of Mantel’s Cromwell seem well-drawn here, and that’s what makes the difference between a series of living Holbeins and a gripping tale. That’s also what makes the difference between museum mannequins and costumed interpreters: emotional authenticity.

No: you cannot get costume and material culture wrong and still claim emotional authenticity as your defense. But the factor that makes a good event or site great is the believability of the characters, and that means more than a lecture on fine details. It means understanding the past, and even admitting what we don’t understand, and seek still to learn.

* Here’s an interesting and tough take on Cromwell’s work destroying the church.

You must be logged in to post a comment.