Lo these many years ago (one dozen) I embarked upon a gown-making folly based on the familiar Oyster Seller image. There was collective interest in this gown 12 years ago, probably because the original painting came up for auction at Christie’s in London. There’s more than one of these out there, and mine was not the best. I am okay with that.

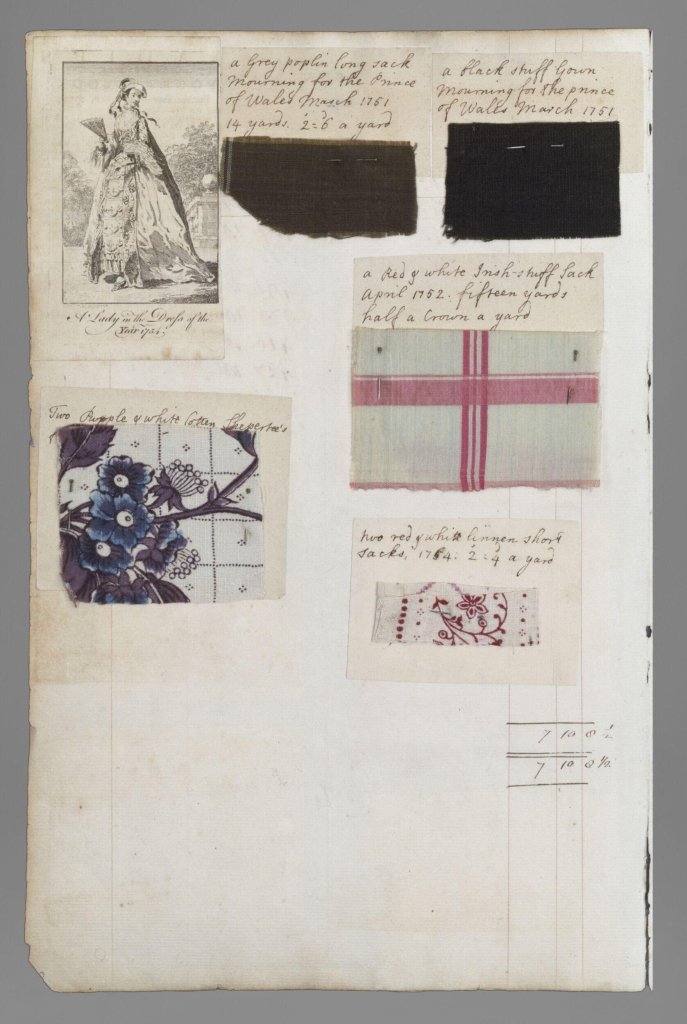

I think we were using the print derived from the painting as a justification for the cross-barred gown, along with a bunch of silk cross-barred sacques. I don’t remember whether or not I’d clicked onto the Barbara Johnson album page with the “red and white Irish [stuff? skiff?] sack, April 1752” swatch. Good stuff, that, and I would be delighted to find fabric like that. However, I had a cross-bar in hand in a form that I did not love.

I didn’t alter the gown at the time because… I was embarrassed by the failure. The person who pointed it out to me was renowned for lack-of-tact, and did not offer any solutions, suggestions, or offer assistance. (That behavior is why people leave all kinds of hobbies, folks. Being kind really ain’t that hard.)

But it is hot this month, and getting hotter. So although I went to storage to look for, and not find, another wardrobe option, I did see this old gown. Did a klaxon sound? A siren? A choir of angels?

Furniture check on an upholsteress? How could I not?

Equipped with more knowledge, and one hopes, more skills, I spent Friday night and part of Saturday disassembling the gown.

What I like about this project is that not only will I end up with a new gown, I’ll have a new gown that is obviously remade from an old gown. Props to me for developing the patience to do this.

It’s not a huge change, but the modifications include making the back pleats actually make sense, and doing them the way Adventures in Mantuamaking taught me to; tweaking the overall silhouette to match the sleeves and cuffs; and adjusting the robings. This should also prevent the various wardrobe malfunctions previously experienced.

I did recut the back lining from fresh linen; the back strikes me as the most critical structural element, so I made sure to replace that. I then stitched a center seam in the upper back, as you do, to mark the center of the back and set the total bodice back length. Overall, the back seemed far too long, and the front too short.

Re-pleated and stitched, the back was ready for new fronts. These required piecing (which is period) and I almost managed it on the lining, but they needed extra work. Even if the piecing is “correct,” it will likely be hidden by an apron.

Fortunately, the sleeves worked with the new bodice shapes, and are actually a better match to the style– they are too narrow for the initial style. I have enough to to rework the robings, but I don’t think I can get a stomacher out of what I have– not unless it’s massively pieced, which is also OK.

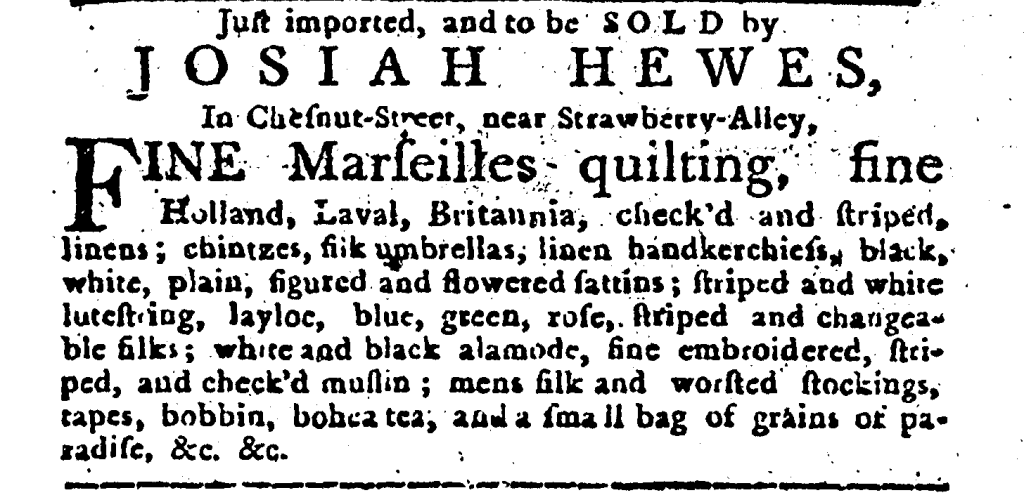

I spent some time digging into Pennsylvania newspaper advertisements looking for checks, check’d, and check fabrics. They’re there– plenty of them– though linen checks for women’s gowns are a lot harder to find. Oops.

Still: I found “check’d mantuas” (silk for gowns) and “Holland, Laval, Britannia, check’d and striped, linens.” Holland linens tend to be heavier, utility linens; Laval designated linen woven in Laval, in Pays de Lorraine (northeastern France), a town noted for fine linens. Could one of those be a lighter-weight check, suitable for a working woman’s gown? (That’s from the Pennsylvania Journal or Weekly Advertiser, December 26, 1781). It’s hard to say there weren’t checked linen gowns, just as it is hard to say there were. The possibility exists, partially because myriad types and patterns of linen were available in Philadelphia, and partially because we lack visual documentation of non-elite women in the Anglo-American colonies.

The runaway ads describe some Scots women and one English servant running away in checked gowns from 1753-1778. This does suggest checked gowns are associated with “lower sorts,” which isn’t exactly what I’m going for, but since I portray a working woman while also not melting, I’ll keep going.

You must be logged in to post a comment.