Last weekend, I had the pleasure of teaching a bed gown workshop at Washington Crossing Historic Park, using a pattern I developed after looking at extant garments, images, and messing about with muslins for several years. What I see– and I know there are different schools of thought– is a shift in the cut of bed gowns over the course of the middle decades of the 18th century. It looks to me as if bed gowns, like gowns, start to have smaller sleeves (for smaller cuffs), and to be a little slimmer in the body.

I’m really happy with bed gown I made, after two earlier iterations (and a wrapper).

The difference is subtle from the front, but the wearing is the test. And I never wore the white one! (Though I still have enough of that fabric to make another bed gown.)

There’s less fabric across the back of the blue bed gown, and I like that better than the more full gown, which I think trends a little earlier than the style of the white one.

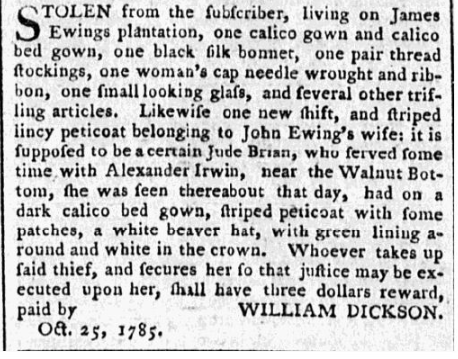

Looking at runaway ads, prints, and extant garments, it began to dawn on me that really, the preferred garment fabric was a print, sometimes printed linen (“washed until the flowers have faded nearly white,” in one instance) but often printed cotton, calico, or chintz. In one ad, a servant wearing a dark calico bed gown ran away with a calico gown and a calico bedgown, and must have made a colorful sight with her striped petticoat– and a small looking glass.

In another instance, a woman ran away wearing a gown and a bedgown, trick I wish I’d known about earlier, for active winter events when a cloak was a hindrance. Reading ads and looking at images in a focused way helped me realize what so many people already grasped: that bed gowns are a seriously useful garment. As one test fitter put it, “It’s comfy, like it’s an 18th century sweatshirt.” Proof that the more we consider something, the better we understand it, and the more we may come to value it.

If you’d like to make your own, the pattern is available on Etsy. Full sized paper pattern includes all sizes A to G (finished bust 30″ to 54″) and illustrated instructions.

Bonus: I got adorable squirrel-themed thank yous that liven up my desktop!

You must be logged in to post a comment.