I had a bit of a surprise when details emerged about the program Sew 18th Century and I will be doing in early March at her workplace. I’ve known about this since late October, but only started focusing on this last weekend, when I realized just how close March really is, and how much time I’ll be spending on well-chlorinated pool decks in February. I’m so glad I asked, because it turns out that we’re reading letters from a family of Quakers. I was not expecting Quakers, and had what is probably a completely inappropriate fabric in mind! (Off-white meandering red floral vines, to mimic a V&A gown.)

Still, there is no surprise that cannot be managed by research. There is an article about the family in Newport History, and they were kind enough to send it to me, and it arrived yesterday. Yay, mail in a small state! The article is helpful in providing context and family history, and there is even a photo, probably from a daguerreotype, of one of the women in the family.

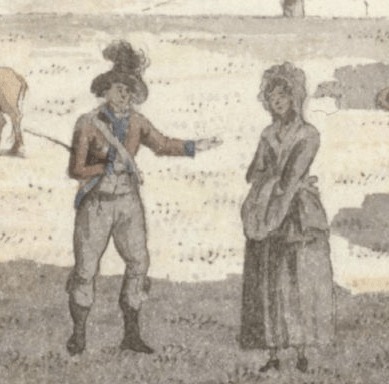

So, what did Quaker women in Newport wear between 1800 and 1820? Lappet caps, for one thing. Lappet caps appear to have been a common cap in late 18th and early 19th century Rhode Island, and Ruth’s silhouette seems to bear that out.

These caps are also seen in many images of Quaker women, and borne out by the images in the collection where I work (sadly not appearing the catalog record, but still stable in the blog post on caps).

I can’t read letters in just a cap and a shift (it’s not that kind of event), so I need a dress. Newport Historical Society has two possibly Quaker gowns from the early 19th century, and they seem like plausible models. But they raise questions quite aside from what you might find out by digging into provenance. What’s up with collars?

The form, a brown or drab front-closing, high-waisted (but not too high) gown, with long sleeves and a pieced, shaped back, is consistent with images of Quaker women from the first quarter of the 19th century. The color and material (brown silk) is consistent with those images, and with earlier im,ages of Philadelphia Quaker women, and that all matches up with a gown that was worn by Sarah Brown of Providence. But the collar is curious, and without putting the garment on a dress form, it’s hard to tell exactly where the collar would fall, and how it would lie.

American, Early 19th century. MFA Boston. 52.1769

This gown at the MFA seems iconic to me, and I can imagine it underneath the white linen, cotton or silk kerchiefs and shawls of the portraits.

To learn more about Quaker aesthetics, I’ll be taking a trip down the hill to the RISD Library sometime this week, to look at books and articles. of particular interest is Quaker Aesthetics: Reflections on a Quaker Ethic in American Design and Consumption, 1720-1920. I’m also interested in an article by Deborah Kraak, Variations on ‘Plainness’: Quaker Dress in 18th Century Philadelphia. It’s not Newport, but at least it’s this continent.

I have read The Quaker: A Study in Costume, by Amelia Mott Gummere, and found it to be a pretty challenging work. It is possible that paint fumes made the writing seem more disjointed than it is, but I thought Gummere’s time-skipping references made it hard to follow the changes in Quaker dress in America, beyond what I do expect from a book published in 1901.

You must be logged in to post a comment.