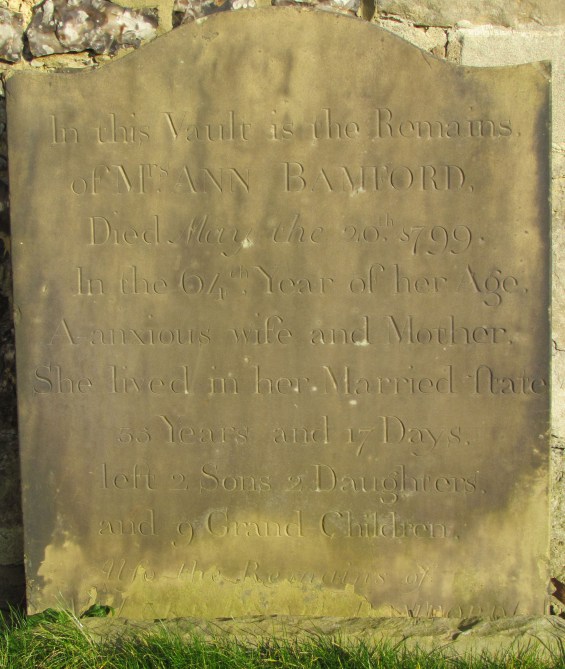

Like Mary Cooley, Mrs. Ann Bamford provides a look into what a woman wore in the 18th century. Born in 1735, Mrs. Bamford’s estate inventory was created after her death at the age of 64 in May, 1799. (She is buried in the St. John the Baptist Churchyard, Borough of Harrow, Greater London. Her gravestone notes she was “An anxious wife and mother,” and records that she was married state to Luke Exall Bamford for 35 years and 17 days. That tells us that the Bamfords married in 1764, when she was 29. I love this detail of the late-20s marriage, actually reasonably typical for women of the period. When Anne Pearson and James Sparks married in 1772, they were roughly 43 and 50, respectively. Older, certainly than Mrs. Bamford when she married (James Sparks’ first marriage was in 1751, when he was 25; and early marriage, but he was by then already a Captain and ship’s master).

Six years, at most, separate the Ann(e)s, Bamford and Sparks. In 1799, Anne Pearson Sparks is 70 or nearly so, married to a former Captain now gentleman and living in England, so the Bamford probate inventory provides a window into what the fashionable and well-to-lady of a certain age might have owned.

The inventory, taken by a man, and now in the collection of the Lewis Walpole Library, may suffer from a lack of feminine insight when it comes to descriptions, but it is comprehensive, listing at least 399 items. It begins:

The inventory, taken by a man, and now in the collection of the Lewis Walpole Library, may suffer from a lack of feminine insight when it comes to descriptions, but it is comprehensive, listing at least 399 items. It begins:

- A Brocaded Sik Nightgown

- A Gold Laced Jacket and Pettycoat silk grosgrain

- A pair of pocket hoops

- Two white petticoats worked at the bottom

- A Black velvet bonnet

- A Black Bombazine Negligee and Pettycoat

- A piece of Printed Muslin for a Gown

- One sprigged muslin nightgown

- One Brocaded silk gown unmadeup

In the entire list, there are (among other things):

- 3 jackets and petticoats, probably riding habits

- 15 gowns and nightgowns

- 5 negligees or sacque-back gowns

- 20 petticoats

- 14 shifts

- 28 pairs of sleeve ruffles (various sizes, some worked, some laced)

- 8 pairs of shoes

- 3 waistcoats; 2 white, 1 fustian

- 45 aprons, cloth, muslin, net, worked and embroidered

- 33 caps, including wired caps and caps “with ribands”

- 4 bonnets, including one in black velvet and one white

- 11 hats

- 26 pairs of stockings, including a pair in green silk

- 3 stomachers

- 12 cloaks

- 58 handkerchiefs of various kinds, some “for wearing,” some worked (embroidered) in gold and silver

- 5 entries described as“gown unmade up”

I love a stack of hats and handkerchiefs, too! Hats & hankies from Burnley & Trowbridge

There’s no reliable way to know when the gowns were made, or what exact style they are. We cannot know the state of all 45 aprons, the styles of all 33 caps, or 4 bonnets. There’s hope in the five gowns “unmade up.” There’s frivolity and impulse purchasing in 58 handkerchiefs. Fifty-eight! 26 pairs of stockings, one pair of green silk, and one pair of thread with clocks, but the majority seem to be worsted.

What does Ann Bamford not have? There are no quilted or matelasse petticoats; this may be a function of the list being made in 1799 when the fashionable shape shifted away from the round bell provided by quilted petticoats, but Ann retains a pair of pocket hoops and has no rumps or pads. The infrastructure of a fashionable shape for the 1780s and 1790s seems missing.

It’s likely that the inventory contains clothing from a range of years, possibly dating back to Ann’s marriage. The brocade gowns may well have been reworked from earlier styles, and the jacket-and-petticoat combination in silk grosgrain with lace sounds like the laced and decorated riding habits of the 1760s when Ann was married. As styles changed in the 1770s and 1780s, she might have had additional riding habits made, since they were worn as traveling and visiting costumes and even at home. There are other clues: the black bombazine nightgown and petticoat and the black silk negligee and petticoat suggest mourning, as do the silver silk negligee and petticoat (there is a second silver silk petticoat as well). These would provide stages of mourning, deepest in black and half in silver. English, Ann’s mourning garb might have been worn for deaths in the royal family (like Barbara Johnson) as well as for her own family. (In this context, negligee describes an informal gown, that is, one worn at home, during the day. Nightgowns, or English gowns, were slightly more formal, for day or evening wear. There are subtle distinctions lost to us, but not entirely dissimilar from our “work to evening” outfits where accessories can change an outfit’s meaning.

You must be logged in to post a comment.