And happy not to be walking to Walloomsac, since we can’t leave till Friday.

Before we leave, there’s plenty to done, of course, and most of it in men’s wear.*

The Young Mr needed a new jacket, a proper one, with pockets and everything, correct for a scalawag. So that meant patterns and muslins and fittings and questions, until neither of us could really stand the other and his father called me an ambush predator of fittings. The only way to fit these wily creatures is, as they amble through the room, to leap out and toile someone.

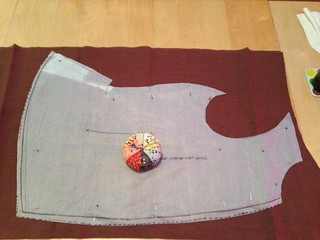

With the pattern more-or-less fitted to the wiggly Young Mr, I cast about for fabric: there was not enough of a striped piece for both waistcoat and jacket; waistcoat won, because matching stripes on a jacket seemed too risky in this great a hurry. Instead, I sacrificed the last yardage once meant for a gown.

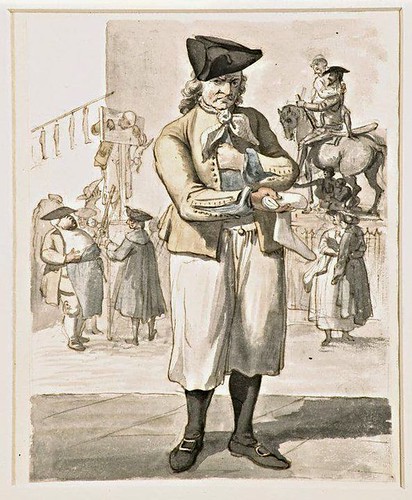

This is the inspiration for the kid’s new garment, along with Sandby’s fish monger. It seems a plausible garment to work from, and the brown linen is in keeping with the brown linen jacket at Connecticut Historical Society and the unlined linen frock coat recently sold at auction. It will also match his trousers, but this is what happens when you sew from the stash.

One pair of breeches altered, one waistcoat wanting the last seven newly-made buttons, one waistcoat in production, one jacket in production: you’d think that would be enough to get done. But I’m also working to expand my cooking repertoire, as bread and cheese gets tiresome and scrounging broken ginger cakes from the Sugar Loafe Baking Co.— while potentially good theatre–is not a solid plan for sustenance.

Boiling food in summer- sounds awful, right? But it’s an easy and correct way to cook,once you translate recipe measures and control the amount you’re making. I like to use Amelia Simmons’ cookbook, because it is specifically American, and my more skillful friends cooked from it at the farm.

From Enos Hitchcock’s diary, I know that he ate a boiled flour pudding with some venison stew (near the Saratoga campaign, I think) so I consider this a plausible recipe for the field, pending eggs, of course.

A boiled Flour Pudding.

One quart milk, 9 eggs, 7 spoons flour, a little salt, put into a strong cloth and boiled three quarters of an hour.

Simple enough, though Simmons later corrected the receipt to 9 spoons of flour, and boil for an hour and a half. I got out the spoon, and looked online at modern boiled pudding recipes, and will give a modified version a whirl sometime this week (always better to fail at home than in the field). Boiling the pudding in a linen cloth in a stew would make a savory bread substitute…and I really liked the one we had at the farm. Will the gentlemen at Bennington like it? Perhaps we’ll find out. If we’re not cooking with hosewater, almost anything should be edible.

*Yes, it’s a terrible and terribly dated show, but I always hear this in Mr Humphries‘ voice from Are You Being Served?

You must be logged in to post a comment.