We’re going up to Minute Man on August 24, or at least that’s the plan. We have hostages to exchange (one ends up with other folks’ spoons and bowls when one does the dishes) and drilling to do for the September 28 event in Boston.

We’re going up to Minute Man on August 24, or at least that’s the plan. We have hostages to exchange (one ends up with other folks’ spoons and bowls when one does the dishes) and drilling to do for the September 28 event in Boston.

Immediately after Sturbridge, the authenticity question blossomed on the interwebs, as there was an unusually fine crop of bodices on view in the village that weekend. (To be clear, I am pro-authenticity and anti-bodice, but I am still working over my thoughts on authenticity, which veered into hermeneutics, and are therefore not really germane to the conversation.)

Authenticity and standards are in the ether, and for this year’s event, all participants are asked to provide documentation, not just the people taking part in the challenge. I plan attend but not to partake of the challenge, as I have no desire to relive my childhood of never-even-third-place, thank you. Instead, I’m merely queasy and scrambling, as the only person in our household who seems really documented to me is the Young Mr, with his snuff-colored trousers currently under construction, and two jackets from which he may be able to choose (presuming I get all buttonhole inspired). So he’s good. Run away!

I’ve been working on a ‘secret’ gown that’s not totally secret, but don’t feel I can adequately document it for this event. I have examples of the fabric advertised for sale, and a period print. But so far, the only gowns of this fabric type described in runaway ads have dark grounds. Granted, servants might tend to wear darker, more dirt-hiding colors, but I don’t feel that one print and some wrong-ground ads are enough. Next!

Anne Carrowle is Philadelphia, not New England: she’s passable for Monmouth and other Mid-Atlantic events. Chintz jackets: also fine for those runaway Dutch servants in NY and Philadelphia. Next!

Brown wool seemed too heavy for August, but the way the weather has been of late, maybe not. Well, anyway, it could get hotter. Next!

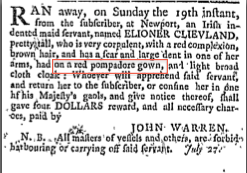

That leaves me with the New Favorite Gown, which I like, but which is based on an earlier British watercolor, so must be slightly altered at the sleeve or cuff as well as documented. At first I could find nothing to suggest that the color and fabric were within the realm of documentary possibility. Eventually I did find an ad in the Newport Mercury for what might be a likely candidate.

That leaves me with the New Favorite Gown, which I like, but which is based on an earlier British watercolor, so must be slightly altered at the sleeve or cuff as well as documented. At first I could find nothing to suggest that the color and fabric were within the realm of documentary possibility. Eventually I did find an ad in the Newport Mercury for what might be a likely candidate.

“Ran away on Sunday the 19th instant, from the subscriber at Newport, an Irish indented maid servant, named Elioner Clievland, pretty tall, who is very corpulent, with a red complexion, brown hair, and has a scar and a large dent in one of her arms, had on a red pompadore gown, and light broadcloth cloak: ” Newport Mercury, 8-10-1772

Two years later, “ a likely tall Negro Woman, known by the name of Violet Shaw, about 25 years old; has a Blemish in one Eye, carried away with her a white Calico Riding Dress, a strip’d Calico Gown, a claret colour’d Poplin Gown, a strip’d blue and white Holland Gown, a Bengal Gown, and many other value Articles…” Boston Evening Post, 8-1-1774

Two years later, “ a likely tall Negro Woman, known by the name of Violet Shaw, about 25 years old; has a Blemish in one Eye, carried away with her a white Calico Riding Dress, a strip’d Calico Gown, a claret colour’d Poplin Gown, a strip’d blue and white Holland Gown, a Bengal Gown, and many other value Articles…” Boston Evening Post, 8-1-1774

Well, I’m tall, and far from 25, but thankfully, I am not corpulent. But here are two wool or wool-blend, gowns, in reddish colors, in the right time period and place. Unfortunately, I have not yet found striped, or striped linsey, petticoats in Rhode Island, Connecticut or Massachusetts in 1772-1775—plenty in Philadelphia, where there are more servants running away—so what to do? I’ll look a damn fool without a petticoat.

There’s the brown petticoat solution. There is one in Boston (Weston), in August, 1774, and another in Newport, in January, 1773. I like the “brown camblet skirt;” I don’t have camblet, but at least the drape of the lightweight wool and cotton will be closer to camblet than to wool. I can agonize over the suitability of fabrics (and the vagaries of style) in some other post.

There’s the brown petticoat solution. There is one in Boston (Weston), in August, 1774, and another in Newport, in January, 1773. I like the “brown camblet skirt;” I don’t have camblet, but at least the drape of the lightweight wool and cotton will be closer to camblet than to wool. I can agonize over the suitability of fabrics (and the vagaries of style) in some other post.

I made the gown intending to wear it with a blue and yellow striped as-yet-unmade petticoat (to look like the watercolor), but have some brown wool I can make up instead. Better documented than not (or nude).

You must be logged in to post a comment.