I was recently asked where I found inspiration for my work, and the obvious answer was in my travels, from the arrangement of bannister-back chairs on the wall at the Yale University Art Gallery to men shaving with straight razors on the parade ground at Fort Ticonderoga. There’s a kind of middle-ground answer as well: the National Museum of the Marine Corps.

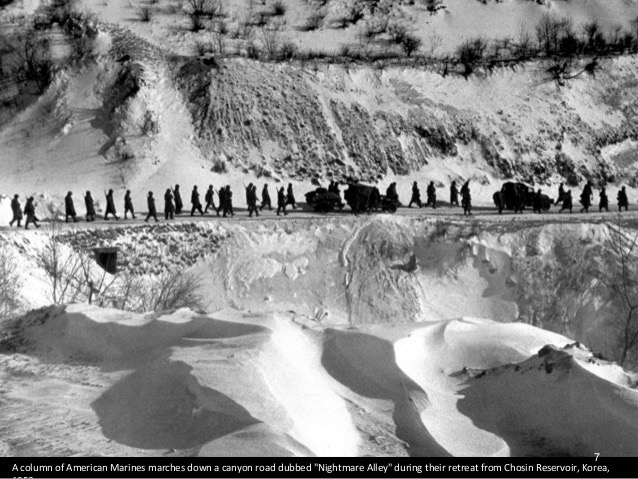

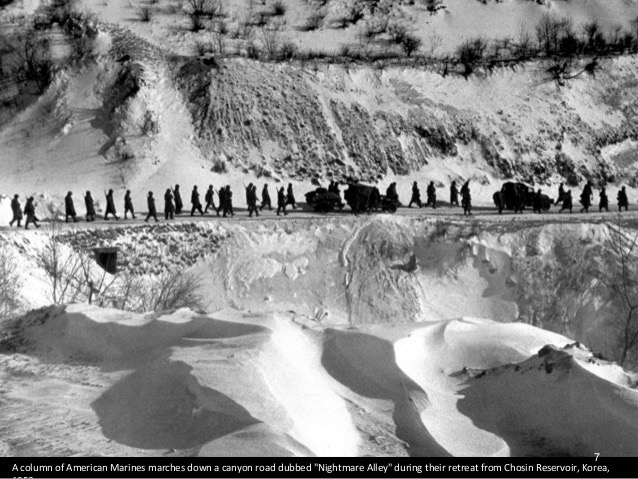

Drunk Tailor took me there almost a year ago, and since What Cheer Day prompted me to think about emotional goals, I’ve wanted to go back. Anna asked about uncomfortable emotions, and while Sharon is absolutely right about the United State Holocaust Memorial Museum being necessary, it was the NMMC’s 20th century displays that came to mind, particularly Chosin and Khe Sanh– Chosin all the more so after watching the American Experience program on the battle of Chosin.

A year ago, the Chosin Reservoir gallery experience resonated with me because it was so well done. Reproductions of David Douglas Duncan photos (he sticks with me because, like Omar Bradley, he came from Missouri) hang on the wall beside two glass doors. To the right, a film runs on a loop, framed by cast resin icicles. Open the doors, and even Drunk Tailor and I are dwarfed by the landscape looming out of the dark. Figures of Marines crouch above us, sheltering behind a snowbank…of dead, frozen Marines. Artillery rounds burst against the dark sky, and I wrap my coat around me because, more than fearful or shocked by the noise and lights, I’m cold. Really cold.

There’s no possible way a gallery –even a Marine Corps Museum gallery– can replicate a fraction of the Chosin experience, but the gallery succeeds in shocking our senses through the simple use of temperature shift, and that is enough to take us out of the everyday. Physical discomfort prompts an emotional shift that allows us to better empathize with, and understand, the experience of the Marine at Chosin. Now, the NMMC and I may have very different takeaways from this gallery: while I absolutely respect and admire the Marine corps (c’mon, I sew OD gowns while binge-watching The Pacific), my instinctive response is No More Wars. That’s a complicated response to have in a military museum, and one I feel more strongly at the NMMC than I have at the West Point Museum.

I attribute these different responses to the greater sophistication of the NMMC compared to the WPM, which presents very standard uniform/flag/weapon/label displays. The NMMC begins that way (the sole “motion” in the earliest galleries is stylized seagulls against a blue sky), and while I love roundabouts and shakos nearly as much as Drunk Tailor, these galleries do not connect us to the history as immediately — as emotionally– as Chosin and Khe Sahn.

Khe Sahn was slightly disappointing this visit compared to last year. To be sure, the helicopter entrance continues to impress me, but I recall the gallery having higher heat and more rats, as well as louder volume. The temperature contrast was particularly notable against Chosin, and I remember taking my coat off in the Khe Sahn gallery last year. Despite those differences, a toddler entering Khe Sahn promptly turned around to leave. The radio noise was clearer this year, and I suspect that the gallery continues to be fine-tuned, as staff attempt to balance the noise of the siege against the noise of the entrance. This is a place where a faint odor of hydraulic fluid lingers in the helicopter, and probably prompted the emotional response Drunk Tailor observed visiting with veterans.

The bottom line, though, is that mindful use of sensory input in any museum can increase visitors’ emotional connection to, and engagement in, the material presented. Visitors are smart: it won’t take much for them to notice a smell, temperature or sound, so even the most cautious museums can sidle into more sensory engagement.

You must be logged in to post a comment.