National Trust Inventory Number 1348749,

What Cheer Day is coming, and I hate to miss an opportunity to make a new gown (despite having just made one, and despite needing to make some waistcoats and trousers for the event). While I lay awake last night, I pondered my options, and whether a half gown would be suitable.

Although I have concluded it probably is not, I was curious about how these should be worn. Where can you wear such a garment? Is it only suitable for at-home use?

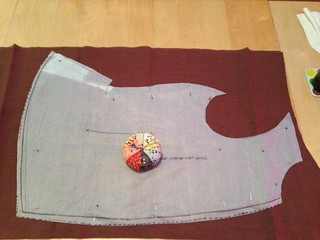

This is the robe from Nancy Bradfield’s Costume in Detail, replicated by Koshka the Cat here, and approximately by me, here.

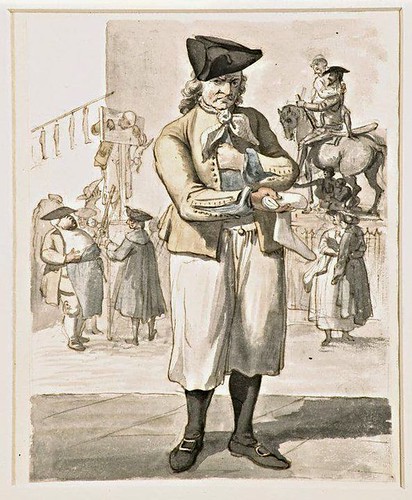

Since I will be a housekeeper again, I think a gown is more correct for me, but that doesn’t stop me thinking about half robes, and whilst scrolling images by year at the Yale Center for British Art, I found this by Cruikshank:

There’s a lot to love in this image, even with its fuzzy “between 1800 and 1811” date. Not only do we get an array of reading material (Novels, Romance, Sermons, Tales, Voyages & Travels, Plays), we get costume tips and– special bonus– a dog gnawing its leg.

(If you are curious about some of the books in the Library at the John Brown House, check out this tumblr bibliography. I’ve been using it of late, and the representative genres are quite similar to what we see in the Cruikshank.)

We also get a chemisette on the lady at the counter, along with a very dashing hat, a fancy tiered necklace on the lady in pink, who also carries a green…umbrella? Parasol? With just a veil, that seems likelier than the longest reticule ever.

I like our Lady in a Half-Robe and her deep-brimmed bonnet showing curls at her brow. She and her companions show the range of white and not-white clothing seen in early 19th century fashion plates, and the range of head wear, too.

The last question I’m asking myself, though, is whether the yellow garment is a half-robe or a short pelisse or a jacket. And can you wear a half robe out of doors? And what did the ladies of the period call that garment?

In this fashion plate (featured by Bradfield on page 84, found by me at the Museum of London), the lady on the right is certainly wearing a short upper body garment, and I’d wager that she’s out of doors or headed that way, since she’s carrying a (green) parasol. Bradfield calls her garment a “jacket,” and until I can find the text of the Ladies’ Monthly Museum for August 1799, perhaps that is the term we should use instead.

While two images aren’t a lot of evidence, it does appear possible to wear a half-robe or jacket out of doors for informal visits in clement weather, and finding two is as good a reason as any to look for more.

You must be logged in to post a comment.