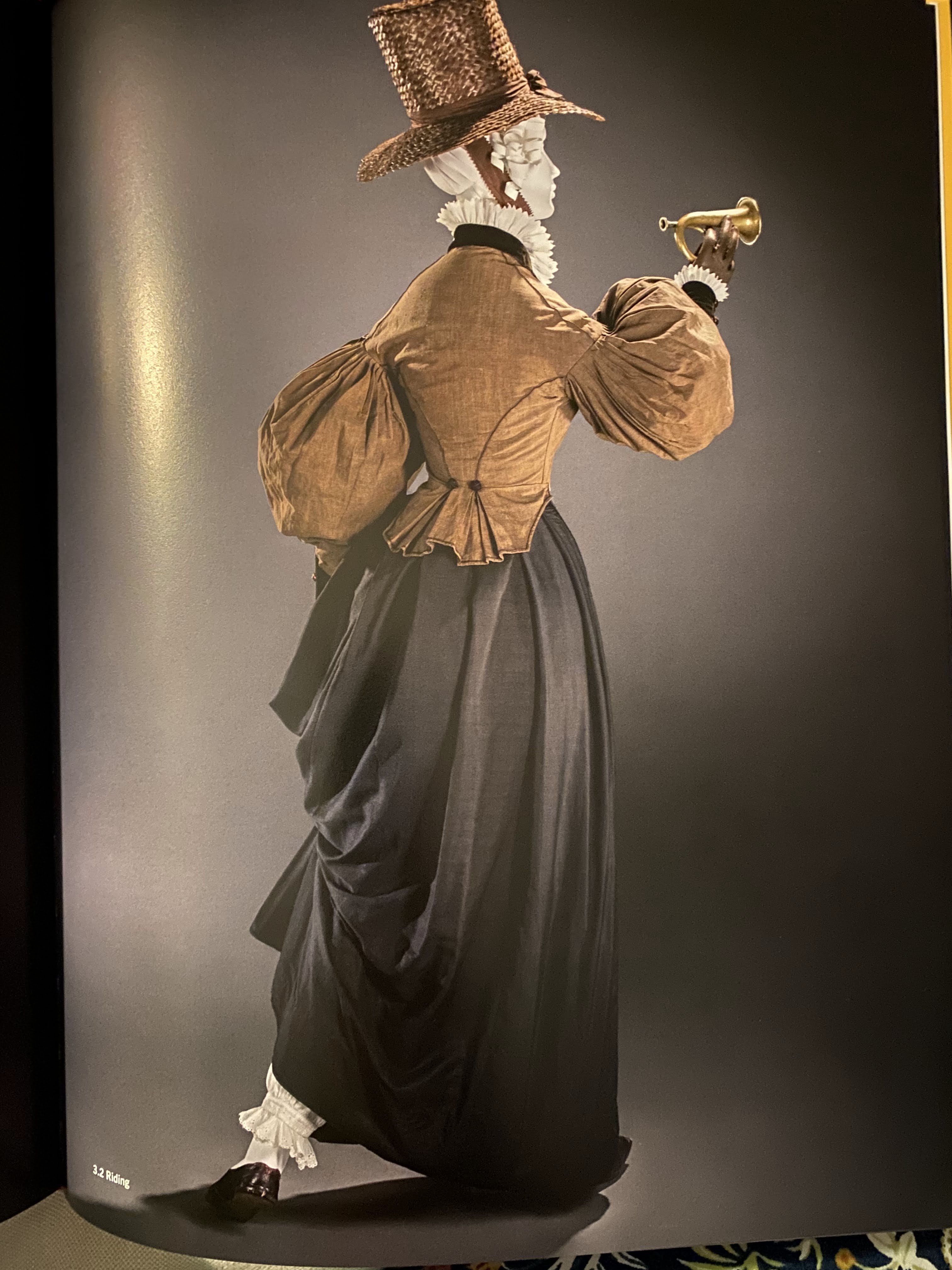

There’s a wonderful exhibit winding up a tour, and although I have not been able (yet?) to see it, the catalog was a Christmas present in 2022. One ensemble in particular captivated me: an 1830s unbleached linen riding jacket worn in Boston, MA. The enormous sleeves and oversized hat probably contributed to my fascination, and with a place to actually wear such a thing, making seemed like a good idea. Or at least an achievable idea.

This journey started in July, 2022, and was finished in August, 2023. Things happened.

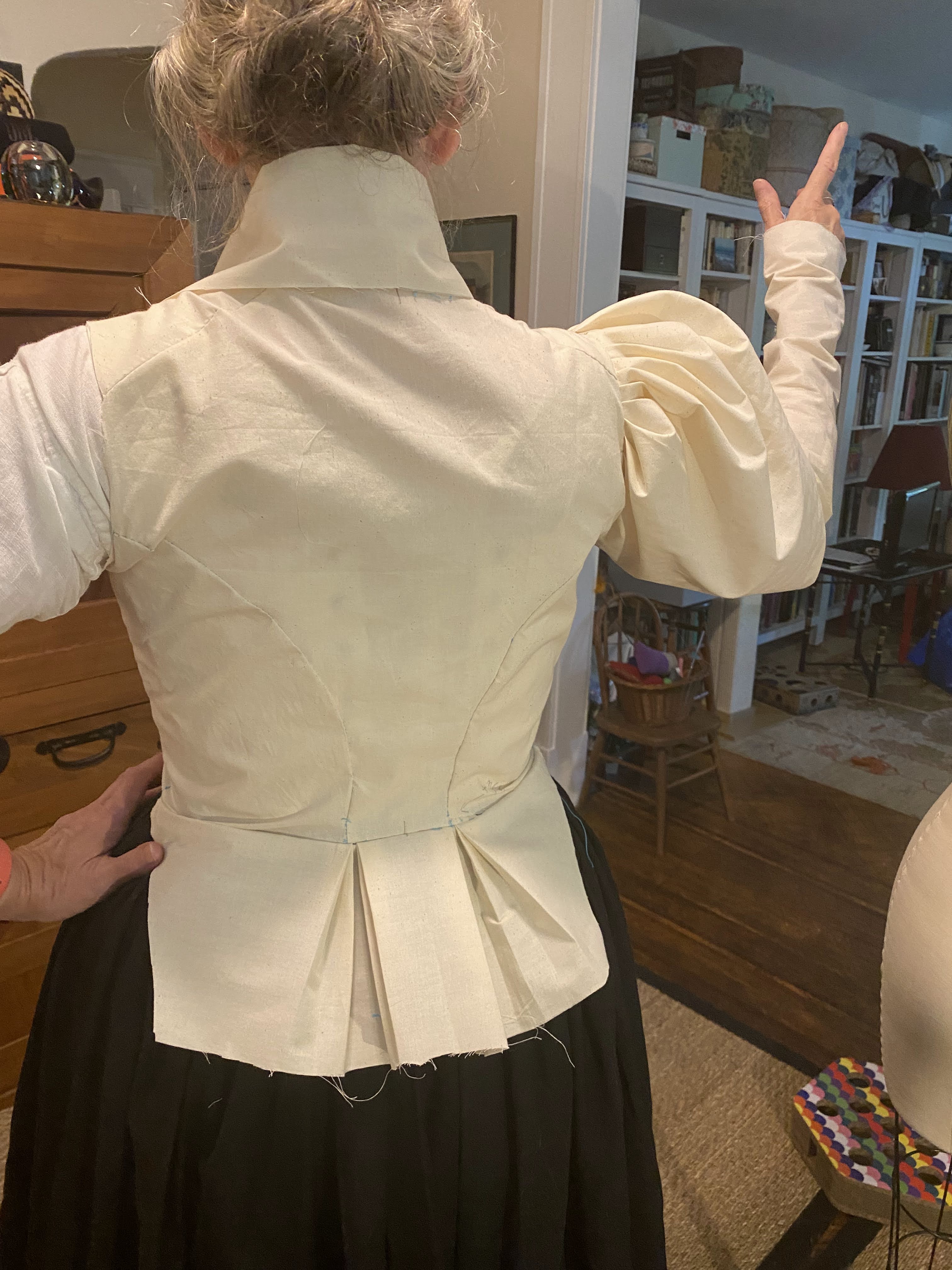

I started with a muslin mock-up, of course, using a previous year’s Spencer a l’Hussard as a starting point. (There is a point when you’ve made enough different things that you can kit-bash your way to many new garments.) The biggest change to the Spencer pattern was in the front closing and collar. The a l’Hussard has a standing collar and fastens with hooks, while this has a fall collar, lapels, and closes with buttons.

There are no published images of the front of the extant jacket, so I looked at both fashion plates and other extant riding habits, ultimately deciding to make a single-breasted jacket.

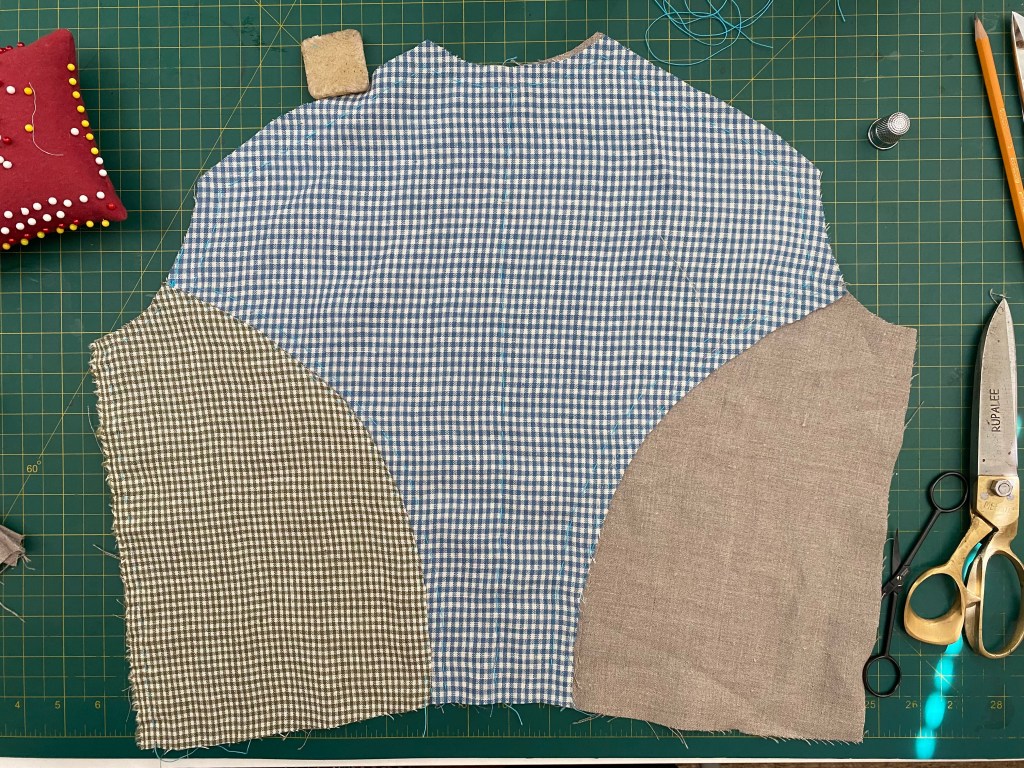

The construction is straightforward, and much like a gown from the period. The bodice is lined, while the sleeves are not. I took advantage of the smaller piece sizes to use up some linen cabbage, and got myself a flashy mis-matched lining as a bonus. One of the trickiest parts was figuring out sleeve supports. I had a melt down over the cage supports, which showed through the lightweight linen and looked awful. I tried them first because I was concerned about the heat down- or wool-filled sleeve puffs would generate for an Labor Day weekend event. In the end, I remembered that I had cotton organdy, and that crumpled up to a nice volume inside some polished cotton covers. These are made with twill tape to attach them to stay straps, if you’re wearing them under a gown; the straps slip over your arms and the puffs rest more or less on your biceps.

Unfortunately, I became anemic while I was making this, and attending a workshop not long before we were supposed to travel to New England wore me out to the extent that we could not travel. Truly annoying, both in thwarted plans and how lousy I felt. Many iron supplements and one appendectomy later, we decided we would make it to the Militia Muster event at Old Sturbridge Village. (It was quite a year.)

To finish this, I stitched on the black wool tape, outlinng back seams, the hem of the peplim, and the front edges. I couldn’t tell from the images whether or not the original had tape, but decided to err on the side of embellished, especially since the cuffs and collar were black velvet. I added custom black velvet buttons embellished with silk thread, made by Blue Cat Buttonworks. Truly lovely, and not within my skill level.

I had planned to wear this with the blue cotton skirt and a riding shirt or habit shirt, but I miscalculated the neck opening and ended up without enough time to restart, so I borrowed a shirt from Mr. K. Luckily the sleeve plumper fit over the shirt, and the jacket fit over all of it! The weather was lovely for early September in New England, and I spent a pleasant day talking about women’s sportswear and the rising interest in physical culture as part of a well-rounded and healthy education in the early 19th century.

The ensemble is accessorized with a black velvet wheel cap, for which Mr. K made the shiny leather brim. The reticule/workbag was made by Anna Worden, and the shoes are black leather Robert Land Regency slippers. The unbleached linen and checked linen lining came from Burnley and Trowbridge, while the skirt fabric came from a Rhode Island mill store remnant table.

You must be logged in to post a comment.