One of things I’ve struggled with in living history is reconciling my own life as a 21st century working woman and feminist with interpreting the lives of 18th century women.

John Singleton Copley (American, 1738–1815) 1769

It takes a while– and a bunch of reading– to get past the notion that these women lack agency in their own lives. Sure, there are notable exceptions: Abigail Adams, Mercy Otis Warren, and Elizabeth Murray, but those wealthy Boston women aren’t the kinds of women I’m interested in portraying. What about more everyday women? What about the women more like me? They’ve proven harder to find, but not unfindable–though even they, by dint of being findable, are more exceptional than the vast majority of 18th century colonial American women.

Elizabeth Weed carried on her husband’s business as a pharmacist, noting that she “had been employed these several years past in preparing [his receipts] herself,” and was therefore well-equipped and trustworthy to carry on in his business. Rebecca Young advertised as a flag maker, and as a contractor, made flags, drum cases, cartridges and shirts for the Continental Army, thanks to her brother Benjamin Flower’s position as a Lieutenant Colonel.

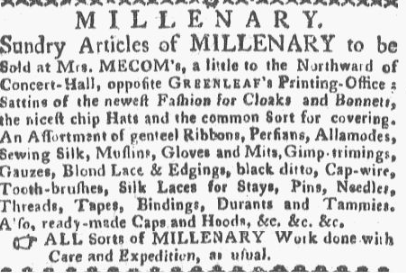

In researching Elizabeth Weed, I read about other women running businesses in Philadelphia, and practicing as “doctoresses” in nearby New Jersey, demonstrating that Mrs. Weed operated in a context of other successful women, including some practicing medicine, or at least “medicinal arts.” What I would really like is to track down the records of a mantua maker or milliner in 18th century America, and not only because I make and sell gowns and bonnets, but because in doing so, I’m carrying on with the kind of work that my grandmother and great aunts did.

For fifty years, my grandmother ran a dress shop in western New York state, dressing the women of Jamestown and the surrounding counties in fashionable and flattering clothes. My aunts made hats and accessories in their own shops, completing the look. I come from a family of makers (including a great-grandmother who made her own shoes), who care deeply about fit and helping people look and feel their best. My grandmother ran a successful shop for fifty years, until she sold it in the mid-1970s. I have many fond memories of sorting costume jewelry upstairs, and gift-wrapping boxes in the basement, with a rack of ribbons in all colors handy on the wall.

She was exceptional in her own way, though you will be hard-pressed to find much (if anything) about her on the interwebs, but maintaining a business through the Depression and World War II was challenging. She gave back, as a member of the YWCA and Women’s Hospital boards, recognizing the importance of sustaining the community you’re part of. When I portray Elizabeth Weed or Rebecca Young, or the Hawthorns of Salem, I think about my grandmother. Maybe it’s a step too far to say the living history work I do or the business I’ve started honors her and the other working women of my family, but I like to think that it helps make visible women who, though now forgotten, were as important to their own communities as she was.

You must be logged in to post a comment.