Watercolor cakes: first invented by William Reeves in 1766 and sold in an improved form in 1780, watercolor cakes made painting easier then before. Colors still had to be ground in water to be used (that’s what the rectangular depression is for in the ceramic palette), but that was a step ahead of grinding the pigments with gum arabic yourself. Each pigment (usually a mineral, sometimes not) requires a specific amount of gum arabic, and in the 18th and early 19th century, both gum arabic and gum tragacanth were both used. In this era of experimentation, even gum hedera (from Hedera helix, or English ivy) was used, both as a diluent for animal glue size and in egg white varnish. The variation in gum types and amounts found in watercolor cakes and cake remains gives us an idea of how much experimentation and variation happened in the pre-industrial era of color production.

Recipes (or receipts) were published beginning at least as early as 1730, with the promise of better, richer, and cheaper colors (qualities that did not always coexist easily). It’s not clear whether the watercolors sold in the American colonies were made locally or imported from Great Britain, but my best guess is that prepared watercolors (sold in shells and out of shells) were probably imported, if only because the sellers so often list many other goods.

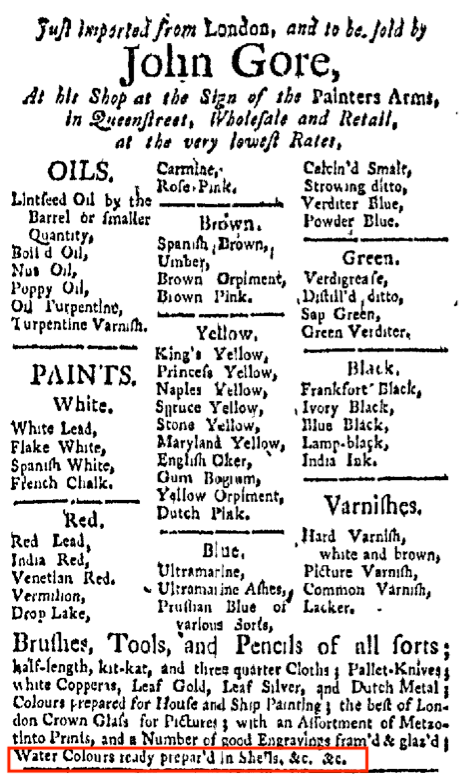

How watercolors are sold evolves over time and varies by place: In 1771 Boston, John Gore, who specializes in artist’s materials at the Sign of the Painters Arms, offers “Water Colours ready prepar’d in Shells” in addition to a variety of artists’ pigments probably ground with different media to each artist’s specifications.

Ten years later, Valentine Nutter, Stationer, offers “water colours in drops, shells, or galley pots,” suggesting that some cakes were prepared in ceramic pots or dishes (gallipots) and available in the United States by 1781. What the “drops, shells, or galley pots” looked like exactly is slightly conjectural: drop are probably corked bladders or bottles; shells are probably cockle shells (watercolor being concentrated means one wouldn’t need a cherrystone clam shell, let alone a quahog) but “galley pots” seem more elusive until you consider the Wedgwood paint chest.

The tiny pots that drop into the oval tray fall within the gallipot definition, and give us an idea of what Mr Nutter might have offered in his New York shop, filled with ground pigment, gum arabic, and a portion of honey to make the cakes re-wettable. Not every artist working in watercolor used honey, as recorded in a 1775 letter from John Singleton Copley to his mother, recording that “Mr. Humphrey tells me he uses no Shugar Candy in his colours.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.