Which came first, the milliner or the polonaise?

Technically, the polonaise. I was supposed to be part of a Burnley & Trowbridge master class way back in … March 2020. Not that year, Satan. Fortunately, it did happen, in August 2022!. I was so glad to be part of the pilot master class for this gown, and back sewing in a class, even as I was intimidated by the form. (I am a maker continually in want of confidence, except for the times when I overextend myself.)

After an introductory lecture, we had a trip to view extant garments at Colonial Williamsburg, which is truly a delight. (I can’t collect 18th-century pieces; only a few early 19th-century things occasionally dip into my price range.)

There’s nothing quite like looking at an original. You can see sloppy stitches and fine sewing, mistakes and alterations, stains, mends, and bright original colors in hidden seam allowances. Every garment tells a story, even without provenance, and sometimes those stumbling stitches give me the confidence to just keep sewing.

Background and References

To understand the history and style of the polonaise, Kendra van Cleave and Brooke Wellborn’s article, “Very Much the Taste and Various are the Makes” (Dress, 39:1, 1-24) is the place to start. Kendra published an accessible summary here, if you can’t access the article. The main thing to know is that the gowns are made much like men’s coats (two back pieces, with pleats; bodice fronts that fall away from the body like a man’s coat, and that meet the back with side seams and pleats) and while the skirts are looped up, looped up skirts do not make a polonaise!

The other thing to know is that these appear earlier than we sometimes think. In the 1771 Louis Carrogis watercolor, both Mmes les Comtesses de Fitz-James et du Nolestin wear polonaise gowns (right). In the English world, the May 1775 Lady’s Magazine describes “nightgowns in the French jacket fashion, flying back, and tying behind with large bunches of ribbons.” (Ladies Dress for May,” 235. (1775). Despise these early references, we know the polonaise is not taking New England by storm, but it does appear in Philadelphia by 1778. This put the form within my interpretive range, so I felt more comfortable tackling the gown: I knew I would have a place to wear it. (What I will do with the redingote underway or the polonaise à coqueluchon I crave remains to be seen; at least the polonaise hoodie is a plausible stretch for Philadelphia.)

To the Making

You get where you need to go however you can

Starting with basic shapes from the last B&T pre-pandemic workshop, updated to reflect the rollercoaster of pandemic weight and tweaked yet again, I cut the backs and stitched the center back seam. The front bodice shape is cut wider, and in one piece with the skirts, as it will be pleated to fit the body. The fullness of the skirts ends up pleated at the side and back seams much the way a man’s coat skirts are pleated, only more generously. So the body of the gown is cut from four main pieces (two fronts, two backs) along with the sleeves and sleeve straps. That’s it. In some ways, this is a simpler form than the English gown, though the fitting feels trickier because it’s not happening in vertical back pleats that many of us default to. It is a gown best made to you by someone else (hence the workshop) or by you on a well-fitted mannequin.

I chose a dark grey silk taffeta from Silk Baron, purchased in November 2019 just after I registered for the class. By the time I was actually packing for class, I’d started a new job, moved to a new city, and helped Drunk Tailor move to a new place. I had no idea where I’d put 8 yards of silk— purchased before prices really jumped. Reader: when we moved BK, I’d stashed it under my bed, handy for the class. I did not rediscover this cleverness until all other locations had been searched and a mild panic had set in.

Beginning

The inspiration was a watercolor drawing by Louis Carrogis of a woman in a black or dark grey gown. Back in 2019, I think I was thinking of a polonaise for a widow, but I don’t recall. In any case, there it was: dark grey silk. Off we went.

The back was simple enough, with a straightforward center seam and inverted box pleats; with that and the lining/front bodice pieces as a foundation, the fronts were pleated to fit. Basting was key to keeping this all in place, and yes, I discovered just how asymmetrical I am.

Stitching the side pleats was straightforward, and satisfying as the gown began to take the polonaise shape. Once the side bodice seams are set, the skirt seams can be stitched (you would’ve basted them already). Then you can start working on the buttons and cords that control the pouf of the skirts.

Much of the shape is determined by the rump, which is essential for this fashionable profile. I used the Scroop Frances Rump largely because it is free and that was much faster than fiddling about patterning this myself. It’s stuffed with horsehair for upholstery, which adds more warmth than you’d expect as you work on this in August in the steamy mid-Atlantic. I also used my red silk quilt petticoat for shape, continuing the warmth theme, and the cat added her fur, just to make sure all the hair and warmth bases were covered.

The sleeves were made from the shape I’d gotten in that last pre-pandemic workshop, so they were pretty easy. Setting them was another matter; fortunately, I had help. The construction from here on is standard 18th-century gown making, with a should strap piece and a binding piece for the back. Cutting the skirts seemed beyond me, so I diverted into a fancy apron.

A Diversion

Sprigged muslin or lawn was a common apron fabric for the decorative aprons worn by the better sorts and seemed appropriate to my milliner. She needed to be fancy but practical since I was imagining this ensemble as comfortable but fashionable workwear. Is there a 21st-century analog? The 20th-century analog for polonaises might be the velour Juicy Couture tracksuits a certain kind of upper-middle-class woman wore to go shopping with friends on a Saturday: expensive, trendy, and comfortable.

I imagined Ann Pearson Sparks projecting her currency in fashion trends by wearing this style while wearing an apron as she trimmed bonnets. That’s a fantasy as far as it goes since I have no immediate evidence of Ann’s clothing, only educated guesses based on readings in costume history and Philadelphia in the 1770s. The apron fabric is a reproduction from Burnley & Trowbridge, trimmed with a plain cotton lawn, also from B&T.

That brought me to October, a full six weeks after I started this project.

Cutting the fronts

I knew I’d initially cut the fronts too long, longer than a fashionable proportion, and I knew, too, that I had to get trimmin’ because this gown had to be wearable in four weeks. (Admittedly, I took another workshop along the way because a spot opened up and I grabbed it.) I started by pinning the fronts to gauge the length I wanted, and then there was nothing to do but trim. The change (improvement) was immediately apparent.

Trim it!

Trimming the fronts also gave me the fabric I needed to trim the gown. I’d decided on self-trim because as much as I love how gauze looks, the hemming seemed insurmountable. My first impulse was to pink the edges and gather the trim. This failed because I could not get sharp pinking irons in the shape I wanted, and my assistant’s tests with pinking shears didn’t look right, somehow. Pinking was abandoned as too much work for the results, so I bought some plain weave silk ribbon, and set about binding the edges.

I needed two widths of ribbon because the trim was scaled, from two inches at the neck and upper bodice opening to four (?) inches at the gown hem, with a full eight inches of ruffle on the petticoat. After starting the trim on October 8, I finished it on November 2. Three and a half weeks, while working full-time and undergoing an outpatient procedure at the end of October. (Yes, I had surgery the Monday before a two-day event, worked full-time, and went to a workshop while addressing debilitating anemia. I am not the most sensible human around.)

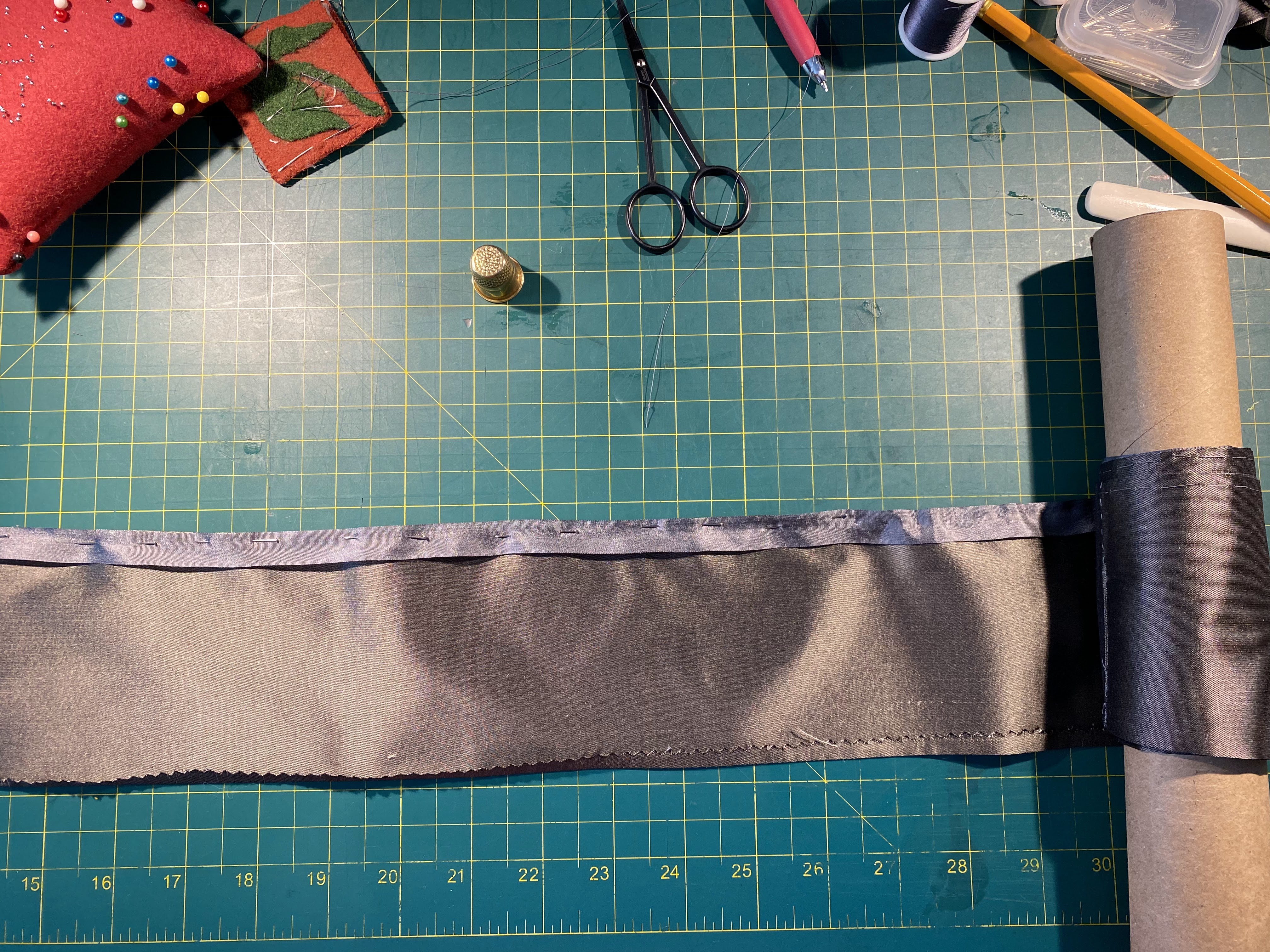

To manage the trim– there were yards and yards of it– I rolled it around empty toilet paper and paper towel tubes. Judge not, this made the wrangling easier. The ribbon was stitched on with silk thread using a running stitch, and the same stitch was used to attach it to the gown.

In the end, it’s probably not as complicated as I thought it was (though I am hesitating before I lay out and cut another one). It is certainly a fun and comfortable gown to wear, and I absolutely love it. It’s delightful to see the skirts behaving the way they’re portrayed in period art, puffing up and filling a chair, thanks both to the rump and the fullness of the skirts.

I accessorized the gown with a silk handkerchief, a cotton gauze cap, and silk mitts as well as the sprigged apron. The handkerchief is pinned closed with a fouled anchor stick pin, which, together with the cap trimming, emulate a Charles Willson Peale portrait at the Met. The hair is as high a roll as I can manage, over a homemade cushion, with hair extensions for fullness and buckles (side curls). High rolls and powdered hair were the very thing in 1777 Philadelphia, so I knew I had to manage it somehow. The Cadwaladers once purchased 12 pounds of hair powder from Ann Pearson’s sister Mary Symonds, so obviously, hair powder was required. While 12 pounds initially seemed excessive, by the time I’d done my hair twice, 12 pounds seemed like it could go pretty fast.

You must be logged in to post a comment.