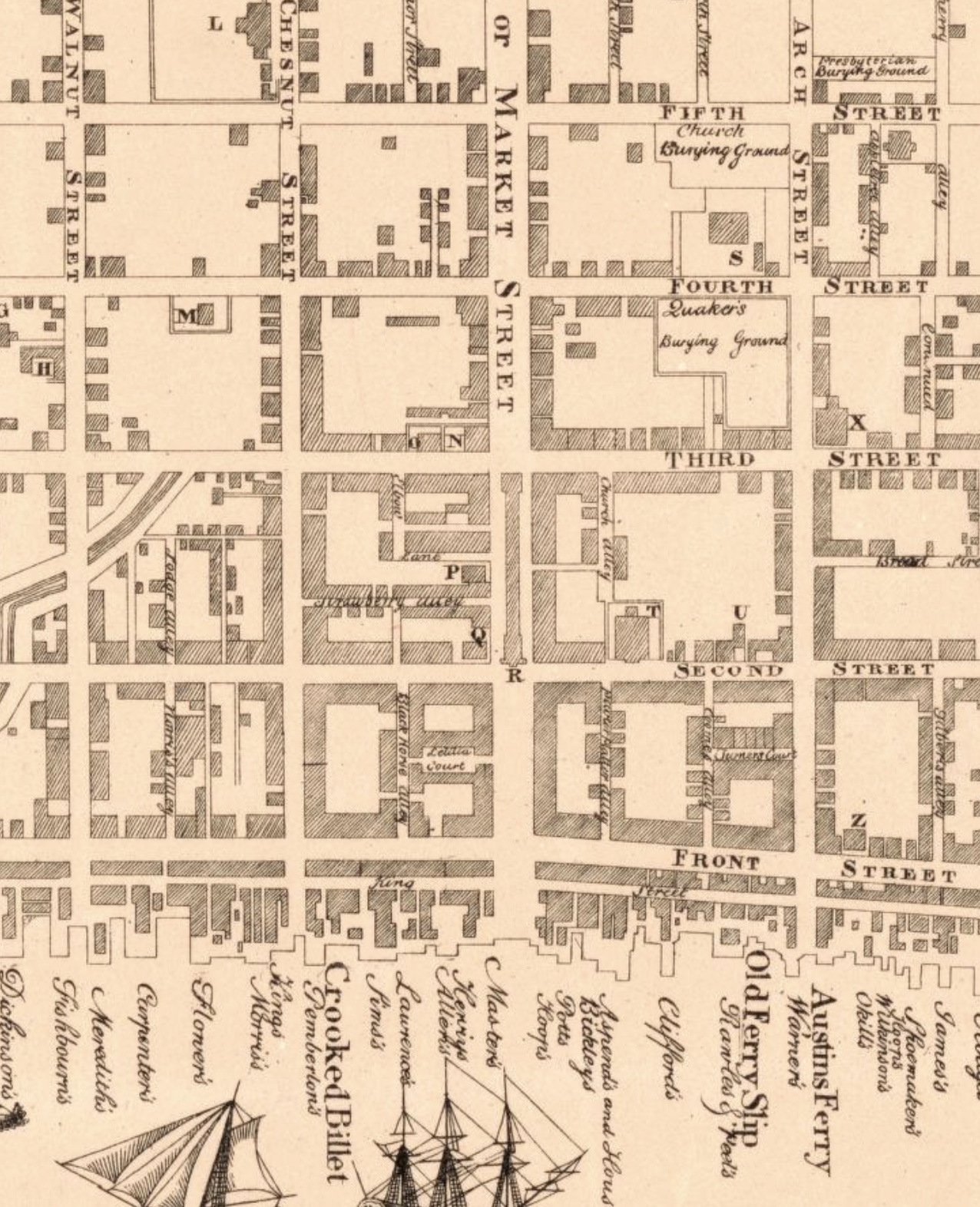

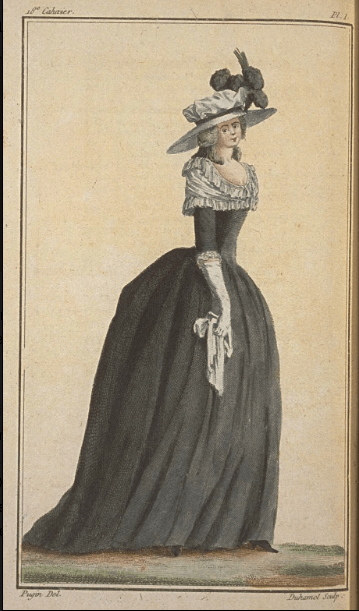

In representing Magdalen Devine at the Museum of the American Revolution’s Revolutionary Philadelphia event, I decided to make a brown silk gown. This is an easy and solid choice for nearly any (every) woman in any location in the Anglo-American colonies in the latter half of the eighteenth century. If you want another option, go blue. But the reason I chose brown is not just because it’s common, or because I have achieved a certain age, but because both Magdalen Devine and Anne Pearson, although members of the Church of England, were associated with prominent Quakers.

Magdalen Devine, known to Elizabeth Drinker as “Dilly,” accompanied Drinker on trips to Bath at Bristol, Pennsylvania, where the two visited the waters. In what is now Bucks County, these baths were chalybeate or ferruginous, meaning they contained iron salts. These mineral baths, initially described as “nasty,” were eventually sought for their medicinal uses. (There is a handy book on American spring resorts called They Took to the Waters: the Forgotten Mineral Spring Resorts of New Jersey and nearby Pennsylvania and Delaware.)

Devine and Drinker visited Bath several times in July and August of 1771. Drinker seemed hesitant to take to the waters at first, and while it is not clear whether “Dilly” helped her overcome her nervousness, the two made multiple trips over the course of several weeks. Eventually, Drinker recorded sharing a bed with Devine, so the two must have achieved a level of comfort, if not friendly intimacy, with each other. (You can read the diary entries here.)

There is nothing in Drinker’s diary to suggest Devine’s appearance or clothing, which, although disappointing, is normal for a diary of the period. But this level of comfort suggests that Devine projected a pleasing, non-jarring appearance and blended in with Drinker and her family and friends fairly well. This could easily be achieved in a brown, grey, or other dull-colored gown. Any of these colors would have been appropriate for Devine, who by 1771 was likely in or approaching her 50s, having been married in Dublin in 1748. (Lest you think Dublin means Catholic, Devine was married at Saint Catherine’s Church, https://www.saintcatherines.ie/our-story, an Anglican church originally built in 1185 and rebuilt in 1769. The Catholic St. Catherine’s in Dublin was completed in 1858.)

Similarly, milliner and trader Anne Pearson is recorded visiting Dr. John Fothergill in London in February 1771. Fothergill wrote to James Pemberton of Philadelphia:

“Dear Friend,

I have just got the enclosed in time to send by our valuable acquaintance Nancy Pearson, who has been so obliging as to see us as often as her business would permit. We were pleased with it as she acts the part of a mutual Friend; brings us an account of our esteemed Friends with you, and carries back all the intelligence she can get that may be acceptable to you.” Pemberton Papers, Etting Collection, II, 65, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

I know this is Anne Pearson, because she wrote to William Logan of Pennsylvania describing her meeting with Dr. Fothergill. Anne was known as “Nancy” to her mother and family. “Nancy” is described in a footnote by editors as “A Quakeress, well esteemed in her ministry,” but I believe they have mistaken the meaning of “mutual Friend.”

Did Fothergill assume Anne was a Quaker because she came from Philadelphia? Or did she dress in a manner that suggested she was a Quaker? It would have been easy enough to achieve a level of “plain” dressing with a brown gown and simple accessories like a white handkerchief and apron, and a lappet cap or a relatively unadorned cap. Did Anne and Magdalen (Nancy and Dilly) dress in ways that made their Quaker customers feel at ease? It would be possible to dress both plain and well, with neatly made fine accessories that would appeal to the eyes and instincts of Quakers and Anglicans alike. Perhaps. While there is no way to know for certain, and two passages do not make data, they do suggest something about these businesswomen and their ability to move among and between distinct groups.

You must be logged in to post a comment.