Ever on the track of laundresses and working women, I came upon The Project Gutenberg EBook of The History of Modern Painting, Volume 1 (of 4), by Richard Muther. I was rewarded with a laundress and a cook holding a spider. Daniel Chodowiecki, a German artist, seems to have been as drawn to the common people as Paul Sandby. The caveat of course is that is he German, so details may not always be correct for American interpretations (pinner aprons, for example).

Still, we have the classic washtub-on-a-table set up, and the laundress is barefoot, which makes very good sense, though my feet hurt just from thinking about standing barefoot on the stubble of the field at Saratoga.

Laundresses come with style, too, though I am asking myself, “Is that a fabulous hat, or is your head just in front of some balled-up, sleeping livestock?” Was is discernible is that her hair is down, and she is leaning on the washtub. The tent seams are also clearly visible, and she does have the iconic washtub on a table set up.

In another detail of the same image, we have a woman who is clearly wearing a black bonnet, tending a kettle on a fire. Here’s yet another piece of evidence for the three sticks-two kettles-no matches set up, and for the tinned kettles being left to get black on the outside.

What is she wearing on her body? There’s a white (or a least white-grounded) kerchief, and what looks like a grey or drab petticoat. But is that a short gown, jacket or bed gown? I’d say jacket, mostly because of the fit, but it’s hard to say at this distance. Whatever word you care to use, she’s wearing a reddish-brown garment fitted to her torso that appears to have a side-back seam.

Once again, tent seams are visible. This tent, just like the one in the other detail, also has some large off-white item thrown over the end. Could it be a blanket, out to air in the sun?

I do also appreciate the short blue jacket/white trousers of the man or boy to the left of the woman, since I know a guy who possesses those clothes and prefers trousers to breeches. He appears to be drinking from a cup as he carries a kettle, presumably of fresh water.

The entire view of the Loyalists’ camp is here, with a zoomable image. The drawing is full of details applicable to camp life interpretations, from women’s bonnets to fishing rods.

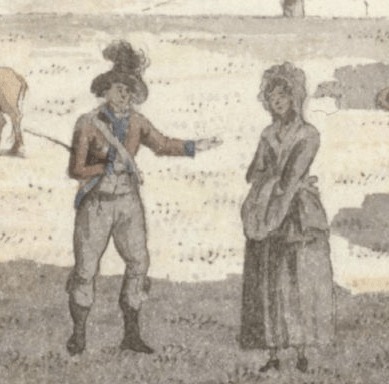

As I contemplate the troublesome Bridget Mahoney, I find the detail below of a solder and a woman rather pleasing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.