We are making No. 5 in this plate from British Flags, Their Early History, and Their Development at Sea… by William Perrin (Cambridge University Press, 1922)

We are making No. 5 in this plate from British Flags, Their Early History, and Their Development at Sea… by William Perrin (Cambridge University Press, 1922)

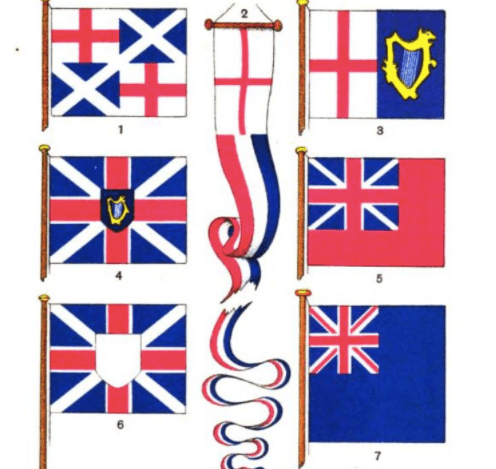

The ensign we’ll be stitching is figure 5 in the plate at left. The first question you might have is, why does this flag look the way it does? Why is there a Union Jack (that doesn’t look like a Union Jack) on a red field? Shouldn’t it be blue, like Tecumseh’s flag? Or just a Union Jack? Happily, the Museum supplied documentation.

From William Falconer’s Universal Dictionary of the Marine (1769):

Ensign: “a large standard, or banner, hoisted on a long pole erected over the poop, and called the ensign-staff. The ensign is used to distinguish the ships of different nations from each other, as also to characterise the different squadrons of the navy. The British ensign in ships of war is known by a double cross, viz. that of St. George and St. Andrew, formed into an union, upon a field which is either red, white, or blue.”

In that definition, we have the double cross, St. George (the red vertical/horizontal cross) and St. Andrew (the white diagonal cross) that form the core components of the canton of the British ensign I’m making. The red field was seen as early as 1707, and the layered crosses were the standard from the union flag of 1606 and 1707. This red-fielded British ensign flag was for use outside home waters, which did not include the North American colonies. (This attitude– that the American colonies were not “home,” and its inhabitants were not “British,” was part of what fueled the Revolution.)

Carmine, Joseph, “Tableau de tous les pavillons qu l’on arbore sur les vaisseaux dand les quatre parties du monde” (1781). Prints, Drawings and Watercolors from the Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection. Brown Digital Repository. Brown University Library.

Carmine, Joseph, “Tableau de tous les pavillons qu l’on arbore sur les vaisseaux dand les quatre parties du monde” (1781). Prints, Drawings and Watercolors from the Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection. Brown Digital Repository. Brown University Library.

Satisfied that I had enough of an understanding to start making, I unpacked the box.