Part five: portraying Widow Weed

I almost prefer first person interpretation, largely because it catches visitors a little off-guard, excites their curiosity, and allows me to use more humor in conversation than third person. This time, though, I found that despite the research and thinking I’d put into this portrayal, I couldn’t synthesize the material fast enough to fully immerse myself in first person, having over-scheduled the days leading up to Occupied Philadelphia.

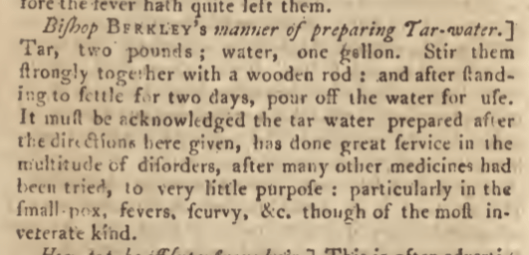

Over the course of talking to 1200 to 1500 people, I was able to synthesize the material, and refine my spiel. Talking about how the remedies could be (relatively) easily made in the kitchen, using ingredients drawn from kitchen gardens, South America, the Caribbean, India and Southeast Asia allowed me to talk about trade networks and the British Empire– a reasonable segue to complaining about a port closed thanks to Mr. Nevell, and a way to explain the effect that has on the city.

One of the most interesting aspects of this portrayal is how well women engaged with it– and enjoyed hearing about a woman with her own business. True, Drunk Tailor was steering women my way, but they also seemed to gravitate on their own. As much as I prefer in situ interpretation over the science fair table style, a table (or counter) offers enough of a barrier to make people feel comfortable approaching. On-street interactions are different, but somehow, indoors, people sometimes react as if one was perfume-spraying staff on a department store cosmetics floor.

Not that scent wasn’t an excellent way to engage people! I couldn’t let visitors taste the remedies, but they could smell them, offering the opportunity to play “What’s that smell?” (non-feline edition) and talk about how people use the flavors they’re accustomed to in their medications and treatments. My cats never cared for bubble-gum flavored amoxicillin, but it’s bigger hit with toddlers than the straight-up medicine flavor would be. So, too, with tooth powders past: cinnamon, mace, and nutmeg are the blue raspberry of the yesteryear– though the tooth powders smell much better than they taste. I cannot recommend a weekend of use unless you wish to feel sad each time you clean your teeth.

Drunk Tailor used the relationship between Thomas Nevell and Elizabeth Weed (their third marriage each) to move people around the main room of Carpenters Hall, and to some comic, as well as interpretive, effect. It’s far easier for him to say, “Six months in, six months left, of her mourning” as a means of explaining the grey and black palette of my clothes, allowing me to avoid the “You look like you’re ready for Thanksgiving!” lead in from the public. Confiding in the public that he’s had his eye on me for while lets them in on a secret, and visitors enjoyed trotting over to warn me about his interest, and that’s he’s sold his tools! I am always happy to tell them he’s just the kind of man my mother warned me about, adapting a banter we have used in multiple scenarios. While it’s broad, and nothing like how we really are together, it’s playful enough to engage the public, relax them, and get them comfortable asking questions.

There are, as always, things I’d like to change about this presentation. Although I’d like to work on it enough to be more comfortable in first person, I’d miss the third-person ability to refer to 1849 cholera maps and general epidemiology. I definitely need to add a couple inches to the hem of the gown, up my cap game, and trim the mantelet. I’d like to find a wooden box, and add a proper mortar and pestle to the kit– my stainless steel one is perfect for home, but won’t work in public. But on the whole, I’m pleased to have an impression of a woman roughly my age, who can interact well with a character roughly Drunk Tailor’s age. Onward to refinements.

You must be logged in to post a comment.