My personal interwebs have been hating on Sons of Liberty, but I’ve left it alone, largely because I haven’t found the forty-syllable German word for “enjoying watching someone else enjoy hating something.” My FB feed exploded with meta-schadenfreude, but really: hating on that show is so easy it’s cruel.

Still, all that chatter did get me wondering: what about Wolf Hall? No, I haven’t yet gone proxy server and watched it on the BBC iPlayer, but I have been following along on the Twitterz and this turned up in my TL: Wolf Hall May be Historically Accurate, but it’s also A Bit Dull.

Except I think the author destroys the accuracy bit. First there’s this:

Peter Ackroyd audaciously asks us to imagine pre-Reformation London as the street markets of Marrakesh. Cheapside would have been a bustling surge of traders and customers, alive with noise and smells, packed with barrels and panniers of fish, fruit and spices, more like a bazaar than the modern city. Equally, to imagine the interiors of English churches in the 1520s, think Andalusian gaudy rather than Hawksmoor’s classicist austerity, the walls covered in brightly painted scenes, the chapels filled with statuary and icons.

And this:

Early Tudor London was a bright, brash and bustling place, unlike its whitewashed Protestant successor, and its inhabitants behaved in similarly extravagant fashion. Foreign ambassadors were surprised by Englishmen’s capacity to weep openly and publicly at the slightest provocation. Satirists condemned the aristocracy and burghers for wearing too much bling: flaunting their status in chains of gold so heavy you were amazed they could walk at all.

Then this:

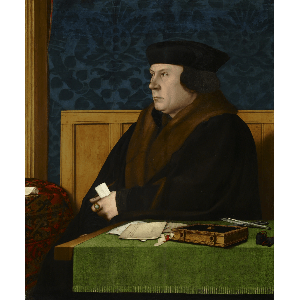

the costumes, beautifully designed and no doubt scrupulously researched, make Tudor society less, rather than more, intelligible. Only Cardinal Wolsey (a melancholic Jonathan Pryce) and Henry VIII (Damian Lewis on imperious form) are allowed bright colours. Everyone else, aristocrat and commoner alike, wear gowns in muted blacks, browns and greens, and so all look much the same – especially as so many scenes take place in near-darkness.

The past sure was a drab place, at least as seen on TV. That’s how you know it’s history! And if the show was so well-researched, why are the costumes so wrong? Because they’re costumes.

Cassidy has gone into good detail about how costume design for a movie or TV programs isn’t about accuracy: it’s about interpretation. And that’s where Sons of Liberty, Wolf Hall, Pride and (or &) Prejudice or Your Favorite Hobby Horse diverge wildly from interpretation in living history. We’re interpreting the past, they’re interpreting a script. (Yes, a script: Sons of Liberty is no way a documentary.)

So I’d save your ire for historic sites and museums and documentaries: what you see on TV is all drama, and just drama. The costuming (and, often, material culture) will in no way be accurate, because it is always designed to further the dramatic goals, and not the accurate depiction of an moment in time.

And that’s why Wolf Hall can be accurate and dull, correct and incorrect. Costume and production designers and directors want us to get the point of the story, so they’ll create dullness where there should be color to make sure we can “read” an otherwise unreadable scene. Now, between you and me, I think good writing can explicate all those class and origin relationships, and that actions large and subtle will show me the emotional relationships, but that’s asking a lot of people who wrecked Mantel’s amazing writing.

In the novel, Mantel has master and servant embrace each other in fleeting triumph. When the dukes go, Wolsey turns and hugs him, his face gleeful. Though it is the last of their victories and they know it, it is important to show ingenuity; 24 hours is worth buying when the king is so changeable. Besides, they enjoyed it. “Master of the Rolls”, Wolsey says, “did you know that, or did you make it up?”

In the adaptation, on the other hand, Wolsey stays seated and Cromwell stands, invisible behind him.

– Did you know that, or did you make it up?

– They’ll be back in a day.

– Well, these days 24 hours feels like a victory.

In the end, I may skip the BBC’s Wolf Hall and re-read the novels. It’s a lot less shouty.

You must be logged in to post a comment.