There was a Very Bad Summer when much was awry at work, the flat we were living in was for sale, my father was moving far away, and the Howling Assistant was sick. In response, I baked.

Things are roiling in the world of late, both at work and in the wider world (I am from St. Louis, and cannot ignore the news from Ferguson), and so again, I turned to baking. Eggs, flour, sugar: what could be sweeter?

A friend tried Amelia Simmons‘ Diet bread a few years ago, with limited success, but the simplicity of the receipt has always appealed to me.

Once again, I risked early morning baking, but I think this has turned out OK. I had to leave for work before it was cool enough to really eat, but a corner was delicious! The intense amount of sugar– a full pound!– was intimidating, the rose water curious when tested, but combined with the cinnamon, seems to have a pleasant and slightly exotic flavour.*

The simplicity of the ingredients was encouraging, but I probably would not have jumped into this had I not found someone else had leaped before me.

Kathleen Gudmundsson on the Historical Cooking Project blog tackled diet bread in May. From her work, I took the tip to use only six eggs.

Following Gudmundsson thoughts at the end of her entry, I beat the egg yolks separately, intending to add the stiff-peaked whites at the end. Half way through adding the flour, the batter became extremely stiff and sticky, and nearly unmanageable, so I beat a whole seventh egg and added that, followed by a little flour and 1/4 of the beaten whites. I alternated flour and egg whites, finishing with egg whites, and found the mixture retained pliability and texture.

Like Gudmundsson, I also lined a glass pan with parchment paper, but my (electric, rental-quality) oven runs a little slow, so baked for 30 minutes at 400F.

The results look like hers, and since she thought the cake was as good or better three days after she’d made it, my hopes for an interesting dessert remain intact.

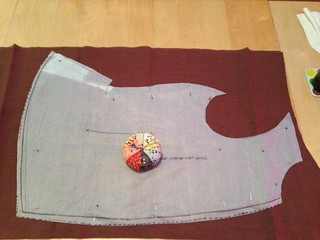

The other, less distracting, project I’ve taken on this week is a set of bags for coffee and food stuffs.

After all, there are no ziplock bags or plastic tubs in 1777, and full complement of graduated tin canisters seems unlikely to plummet into my lap anytime soon. The two slender bags are for coffee: tied at the neck, they’ll hold enough for cold coffee and fit the slender tin coffee pot we have, sparing the larger cloths, wrangling grounds, and giving us clear, cold, caffeine. Another is for flour, one could be for oatmeal, another for sugar. In any case, things to eat are getting wrangled in a way that can remain visible in camp.

I know: a trifle mad, but the time I spend now makes living in public so much easier when there’s less to hide. And yes, before you ask: that will be a real fire.

*Fellow eaters, you’ve been warned.

You must be logged in to post a comment.